|

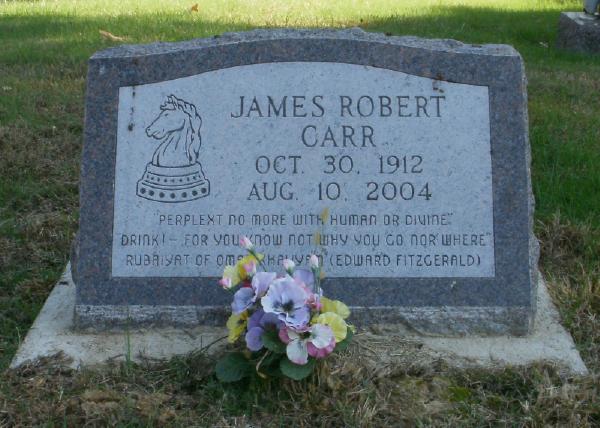

JAMES ROBERT CARR

|

30 October, 1912 -- 10

August, 2004

A TRIBUTE TO MY FATHER

Biographical Sketch

by William R. Carr

James Carr was born in 1912, only a dozen years into the the twentieth century. Automobiles were novel sights on the streets of Harrisburg, Illinois when he was a young child. Civil War veterans were still among the old folks, and talking movies hadn't yet been heard of.

Even as a young child, James was very independent minded, and

therefore always sort of the black sheep of the family. Youngest among three

children who were raised by grandparents, he was always the "lesser"

member of the family, and apparently was never allowed, or able, to forget it.

Older brother George was the family favorite

— the one expected to enhance the family's standing in the world. George had

the right attitude, and he was practical, in addition to being talented. James,

while also very talented, was the perennial underdog — and, to make matters

worse, he often had doubts about things that others took for granted.

The family was from the Stonefort area, southwest of

Harrisburg and the extended family and network of close friends extended south

to New Burnside. James was named after James Taylor, of New Burnside, a

businessman and barber. James' paternal lines were Potts and Barber. His

maternal lines were Gurleys, Wrights, and Camdens. His father was Joseph Potts,

of Ledford, and his mother, Sybil Gurley, of Stonefort. His last name was

changed when Sybil's second husband, George Carr, formally adopted her three

children in 1918. There were some unfortunate stains on the Potts name in

Harrisburg and Southern Illinois, so the change of names was a welcome one.

Though born in Harrisburg, James' earliest memories are of a

farm about two miles west of Stonefort. He and his brother and sister, George

and Flo, started school at Henshaw school nearby. The family moved to Gaskin's

City (now part of Harrisburg), when he was about five or six, and later to 503

East Church Street in Harrisburg (a house that still stands). For a short

while James lived with his mother and adopted father in Mt. Carmel, Illinois,

but moved back with his grandparents in Harrisburg before long. He attended

elementary at Logan School and graduated from Harrisburg Township High

School. About that time (1930), when he was 18, the family moved to a farm

James' uncle Bill bought a mile south of Rudement, off Illinois Route 34.

While similarly talented, George and James were as

different as night and day. George was always the "proper" young man

who was always careful in his dress (almost never seen without a tie), and

always carefully politically correct. James was a nonconformist and tended to be

politically and socially incorrect, always marching to his own drummer. To him,

principle, and personal honor, were much more important than appearances and

what we now call political correctness. The family intended to make a surgeon

out of George and sent him off to the University of Illinois, but James, the

black sheep of the family, had to shift for himself.

"The family" was comprised of grandparents, Greene

and Tran (Wright) Gurley, and his uncle, Bill Gurley. James' mother, Sybil

(having divorced her first husbands and remarried a third), went to beauty

school and became a beautician in Kankakee, Illinois. Sybil tended to defend

James, but was seldom on the scene, as she helped support her children usually

from afar.

|

|

George came close to accidentally shooting James once at the house on East Church Street. Their mother's husband was then Ray Gerard, and, like many during the gangster era, he packed a gun. George found it one day when he and James were home alone. He drew it on James, not realizing it was loaded. Fortunately, he then pointed it at the coal bucket. When he pulled the trigger, there was a loud report and the coal bucket, rather than brother James, was shot.

James' first Summer job, when he was only about ten, was procured for him by his grandmother. It was as an "ice boy" carrying heavy blocks of ice into homes and putting them into ice-boxes from the ice delivery wagon. It was tough work for a boy his age, and he never felt any particular gratitude toward his grandmother for that particular favor.

James' youth was during one of the greatest eras of America's

technological transition. One of the many great changes he witnessed was the the

transition from silent films to talking movies. Until the "talkies"

took over, all theaters had a large pipe organ as one of their necessary and

standard fixtures. It was situated right in front of and below the stage, and an

organist would play music to accompany the movie, with its on screen textual

subtitles and dialogue boxes. When the first "talkie" motion picture

came to Harrisburg (to the Orpheum theater, I believe), James played hooky from

school and was the first in line at the theater to see the new wonder.

He later got a most coveted job at the Orpheum as an usher.

He soon quit, however, when the theater manager (who happened to be the owner's

son), had the crust to suggest that James tie his neck tie a little differently

than he'd been accustomed to wearing it. He even undid the tie for James and

proceeded to retie it in his approved fashion right in the aisle. James was

outraged and would have none of it. He whipped the tie off, told the boss what

he thought of his tie, and stalked out of the theater.

|

|

At the ripe old age of 13, James fibbed about his age and signed up for Citizen Military Training Camp training at Jefferson Barracks, near St. Louis. This military training program during the post World War One era was part of the nation's military preparedness program of the day, and a forerunner the present "Reserve" training system. This was in the days when there were still mounted cavalry based at Jefferson Barracks. James said that a friend, Glen Coffee, was the one who put him onto the Civilian Military Training program. James went a year after Glen first attended. The training lasted one month during the Summer. His second year, he went to Sparta, Wisconsin for field artillery training. There was a "Red, White, and Blue" program, where those who completed the training and intended to pursue a military career in the Army could end up with a 2nd Lieutenant commission. Though James didn't complete the program, he had the distinction of becoming a sergeant before he entered high school.

|

|

|

|

The family was staunchly Baptist, and

James, when he got a few years on him, was given to "free thought" on

religious matters. He marched to a different drummer entirely — not only out

of step with his family, but often with everything around him. He also liked to

imbibe in drink now and then, which was very much frowned upon by at least the

female side of the inner family circle.

To many, his life is the story of exceptional talent

and ability squandered. Though this may be true from a materialistic standpoint,

he has more to his credit than most. In high school manual training class he

made a desk which won top honors wherever it was displayed. His instructor, John

S. Charlton, entered the desk in several manual arts contests throughout the

state and it won top honors, hands-down, everywhere it went. Finally, Mr.

Charlton purchased the desk from his student for $50.00, which was quite a sum

in those days. James used part of the money ($5.00, to be exact), to purchase

his first automobile — a model T.

When James had complained that the mechanical drawing he was

required to do in manual arts class was too elementary, the instructor showed

him one of his own college drawings which had been graded 100% correct. When

James studied the work and pointed out an error, Charlton was initially

flabbergasted at the impertinence, but finding his student to be correct, made

him drawing room foreman.

|

|

|

|

|

|

It may seem strange to those who knew my

dad only during his more sedentary later years, but he was quite an athlete. He

was on the track team one year. He played football with the Harrisburg Bulldogs

and he boxed regularly, for a while, "upstairs" at the Harrisburg City

Hall. He was forced to quit boxing, however, in order to stay on the football

team. School officials considered his extracurricular boxing to be a

"professional" sports activity which would disqualify him from school

sports.

James wasn't inactive in school. He never excelled

academically because, as he said, he had more important things to do than what

the school had to offer. He did excel in such things as art and history. But he

applied himself to most of his studies only to the extent that he usually passed

with average grades.

In addition to playing football and running in track, he did

quite a bit of artwork around the school. He was a member of the

"Keystone" yearbook staff art department. For competitive and academic

purposes, the students at Harrisburg Township High School were divided into two

groups, Emersonians and Lowells. One year he designed the home-coming gym

display for the Emersonians. It was based on an Arabian theme and won top honors

for that year.

|

|

James earned the coveted Harrisburg

athletic "Big 'H'" to wear on his sweater. This seems to have made

George, who did not participate much in athletics, a little envious. Once, when

James was sewing the H on his sweater, George came in. Bobby, a little dog with

whom they had grown up, scratched at the door to get in. George let the dog in

and then gave it a kick that rolled the poor little dog over several times

across the floor. This outraged James, who has always been a great dog lover.

"What did you do that for?" he demanded. At that, George unexpectedly

hauled off and hit James in the face, knocking out one of his front teeth.

As the big brother, George had always made James live hard.

The brothers had fought often as they grew up, and George had always come out on

top because he had always been much bigger. But things where different this

time. James had finally caught up in size, and this time he made his brother

pay. That was their last fight, as George gained a new respect for his

"little brother."

The year he was supposed

to have graduated from high school, he and two classmates, Homer Harper and

Eugene Sisk, looking for a little adventure, took a year off to go "out

west." They freight-trained it to New Mexico, where James worked on a ranch

for a few months. They returned home in the winter, and, at one point, James

found himself stuck on a long haul clinging to the outside of a box car in a

driving snow storm.

Miss Rice (teacher): "Why were the Middle Ages called the dark ages?"

James Carr: "I suppose it was because there were so many knights."

(From 1930 Keystone Yearbook, page 115)

Hand-painted Christmas card

by James Carr

This map was painted when James was in Jr. High School.

|

|

While brother George was sent off to Urbana to study, in the family's hope of producing a surgeon, James had to enroll himself at Southern Illinois University. He only attended for one term, for he felt college was wasting his time. Through the Reader's Digest, he had discovered the curriculum of a certain university which taught exclusively from "The hundred greatest books ever written." The hundred great books were "Listed Chronologically providing a Continuity of Thought" in a four year course of study. The first year spanned Homer (c. 850 B.C.) through Horace (c. 65-8 B.C.). The second year Quintilian (c. 40-118 A.D.) to Descartes (1596-1650). The third year, Corneille (1606-1684) to Gibbon (1737-1794). The fourth year, The Federalist Papers through Trotsky (1879-1940). Over the next several years, and throughout his life, he collected and read most of those books, and some of them he read several times. He was one of the most familiar faces at the Harrisburg Public Library, and claims to have read and re-read most of the books they had that were worth reading.

|

|

|

|

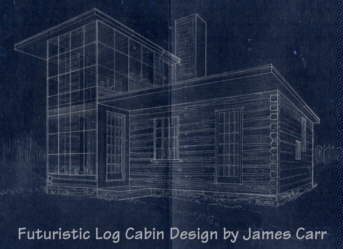

His greatest ambition was to become a

writer, and it was in this direction that he exerted most of his energy, letting

his art and painting talent lay fallow. Most of his drawing was devoted to

architectural drafting. He took correspondence courses in fiction writing. He

wrote many short stories intended for the pulp market, and started at least

one novel, "Lost on Venus."

James had graduated from high school on the eve of the Great

Depression, and in spite of his talent and drive to write, like everybody else,

he found tough sledding. Since he couldn't find work or remuneration in the

writing field that he wanted to work in, he became disillusioned. He found that

people with skills in industrial trades were the ones who got the good jobs. The

liberal arts education he had received in school and continued to pursue on his

own, while making him a well educated young man in the academic sense, had not

paved the way to a good job. He worked several jobs, including the toughest one

he ever had — loading box cars for Sears at Streeter, Illinois, near where his

mother ran a Beauty Shop. Ten hours a day, six days a week, for a dollar a day.

He worked as a show card painter and window dresser at the first supermarket in

Harrisburg (later Uptown Market, now closed). He went to Chicago, where he ran

into former classmate, and later neighbor, Alfred Wasson, and got a job as a

department store window dresser. Then he worked at cabinet making in his

father's (Joseph Potts), Chicago shop. Finally, he went to Pontiac, Michigan and

worked in an automobile plant.

About the time James graduated from high school, his

uncle Bill had purchased a farm a mile south of Rudement and this became family

the headquarters during the depression years. "That was one time Bill made

the right decision," James said, "He could have taken that money and

bought a new automobile with it, but he bought a farm instead." And the farm helped pull the family

through the Great Depression without missing a meal.

In 1934, a group of young Chicago "idealists" came

to the area to set up a "College in

the Hills" just a few miles south of the farm. When he heard of it,

James went down and made their acquaintance. James became friends most

particularly with one "Penny Cent," a young German artist who was one

of the leading members of the group. Penny Cent got George into the WPA Federal

Arts Project, while James finally landed a job with the WPA Federal Writers'

Project.

The local citizenry looked upon the staff of the College in

the Hills with a considerable amount of suspicion, so the enterprise did not

last very long. The locals suspected Penny Cent and his friends of being

communists. The name, Penny Cent (or Pennycent), was enough to make the

"natives" suspicious. And for their part, the college staff, spoke

rather condescendingly about the local natives they had come to educate. The

natives didn't think the educated city kids had anything to offer. As the winds

of war with Nazi Germany began to blow, the German Penny Cent was suspected of

being a German spy.

The college closed down and Penny Cent removed to Harrisburg

where he conducted art classes at this rented home. But the Harrisburg folk were

about as suspicious of him as the country folk had been. Soon Penny Cent felt it

best that he move on. Of all those that Penny Cent had befriended, James Carr

and fellow artist, Paulis McClendon, were the only ones on hand to help Penny

Cent pack his car (a nice new red convertible), and see him off. The politically

correct of the day would no longer associate with him. Penny Cent rode off into

the sunset.

Mildred & James

James married Mildred Inez Goodman

during this period (1936), and started building their home next to the Gurley

farm, on an adjacent piece of land given to him by his uncle. George did

likewise next door.

After his sojourn to Michigan after his

marriage, James returned to Southern Illinois and got a job on the WPA Writer's

project. His assignment was to cover, and write about southern Illinois. He did

research at various libraries, newspaper offices, court houses, etc., and

traveled to the different locations of interests, often with Mildred, writing

historical sketches intended for a travel guide. It is not known whether any of

his work was published.

| From:

The WPA GUIDE TO

ILLINOIS Illinois: Tours — Tour 3A

NOTE (wrc): This was the tour project upon which James

Carr was assigned and worked. Whether the above specific text was

authored by James has not been ascertained, though his surviving notes

indicate that he covered this site. Ironically, Isaiah L. Potts, the

actual owner of Potts Tavern, was James' four times great uncle, but

this Potts connection remained either unknown or a closely guarded secret

throughout his life, and he would be shocked to learn that the secret

is out and published on a public forum. |

When the war interrupted the WPA projects, George joined the army, and James became a guard at the Illinois Ordinance plant at Herrin, where he was the first to get ten bulls eyes out of ten shots, earning an "expert" rating, and best shot among the 50 man force. During his long watches he did a lot of reading. He had a set of little pocket volumes of Shakespeare and other classics, which he and his friend Ike Mehem shared and read. Later he moved to Chicago and was the best shot of another 50 man guard force at a defense aircraft plant just prior to the end of the war.

|

|

Before the war, he was intent on

becoming a pulp writer, which was considered the gateway for all new fiction

writers in those days. The "pulps" were small, cheaply bound, books

which served as a public entertainment medium. They were usually adventure,

romance, or western stories or short novels. But times were tough, as the above

"meal ticket" attests. The economy boomed after the war, but the pulp

market never revived, among other things, due to the growing popularity of radio

entertainment and later television.

James worked on the Writers' Project until the completion of

the Illinois Ordnance Plant near Carbondale. He was one of the first to be hired

on there as a guard.

In 1941, James went from being a WPA writer to Guard at the Illinois Ordnance Plant where he worked until near the war's end. |

Their only son (me —

"Conceived in Infamy," on or about Dec. 7, 1941), was born during the

war, on September 1st, 1942, but the marriage to Mildred was doomed. Two

reasons. Mildred, who loved the farm and the Gurley family, refused to join him

and live in Herrin near his work. Thus, James, a healthy and very handsome young

man, eventually fell into an extramarital romance in Herrin with a woman named

Jewell. Secondly, Mildred fell very much under the influence of James' family,

who were always critical of him. James's sister, Flo, encouraged her to

divorce him, which she did over his protestations.

Mildred took their son to Chicago where Violet, one of her

sisters, was living with her husband, Darwin Catlin. James followed and got on

the guard force at an aircraft factory. After the divorce, James married Jewell,

but the marriage lasted only a couple of years (she wouldn't follow him to

Chicago). The war was soon over, and the world, and everything else had changed.

James tended to be argumentative, especially when

drinking. One of the things he always tried to drive home to his son was,

"Never argue, or even discuss, religion or politics." But he was

quicker than anybody to jump into religious and political argument. He delighted

in tearing down the icons of politics and religion. I guess it never occurred to

him that he might hurt someone's feelings. This tended to make him abrasive and

down-right unsavory to many, and he certainly didn't make many friends at it in

our neck of the Bible Belt. But there were many who respected his views, admired

his learning, and learned considerably from them. His goal, he said, was to

"open closed minds."

|

Certificate of Meritorious Conduct |

It would seem strange to anybody who

knew James during the latter half of his life but, prior to World War II, he

took quite an active interest in politics, supporting the Democratic Party. The

war may ultimately have helped to kill much of my dad's ambition and drive to

succeed in life, for he found that the government could play dirty — or at

least sow the seeds of suspicion which undermined a person's standing in

society. Though he was a staunch Democrat and had been a great supporter of FDR (see

James' political speech), he was vocally outspoken against us going to war

on behalf of the British. He wrote a letter to the editor of U.S. News &

World Report (and probably others), stating his mind on the matter, drawing

a comparison between Franklin Roosevelt and Alcibiades, stating, "we don't

need another Alcibiades," which, of course, wasn't taken as a compliment.

(See Plutarch's Lives)

Before long, government agents were snooping around

Harrisburg "investigating him." Local people began to get the idea

that James might be a German Fifth Columnist, and shied away from him. He

had been a friend of Penny Cent, the

mysterious artist associated with the College of the Hills, who had been

suspected first of being a communist, and then a Nazi spy. A few

"incidents" occurred, such as the time he was followed and beaten in

Chicago, for no apparent reason. Such things turned James into a life-long

cynic, and somewhat of a paranoid for many years. I have been unable to find

James' "Alcibiades" letter, but below is an example of an earlier

letter to the Editor of the another news journal, the United States News.

| December 30, 1940

Editor, "The Yeas and Nays" Dear Sirs: Once upon a time there lived a happy farmer named Republicus "Democus" Americus who, in the throes of growing pains, had build an elaborate dwelling of which he was proud. Ah, but the foolish fellow; he had ruined his credit borrowing talents which he spent lavishly upon interior decoration at the expense of a roof. It is true, at on time Democus did construct an improvised roof which cost him plenty, but thoughtlessly he had allowed this to decay and crumble. But Democus did not worry. He told himself pleasant stories the livelong day, and wallowed in the sunshine of his apple orchard while his friends prayed for rain. Then it came to pass that this happy fellow awoke one morning to find the sky overcast. Looking to the east he beheld a dark cloud rolling toward him. He though of the neglected roof. He must finish it before the storm broke. But alas! How could he obtain building material? He had spent the last borrowed talent paying off the interior decorator. True he had apples, but they were spoiling for want of a buyer. Poor thoughtless man. What could he do? Fortunately, though lacking foresight, this farmer was a man of action. He rushed to a bank, mortgaged his farm, and with the proceeds purchased the building material. Lucky fellow! He was driving the last nail as the storm arrived. Sitting under the new roof, listening to the rain outside, this man of action smiled. His house remained dry. The the storm passed and the sun came out. The happy fellow thought to bask in the sun again as he had loved to do. But alas and alack! Unlucky fellow! He could have no peace of mind. There was that mortgage to worry about. It was coming due. What could he do now? What could he do? Ah cruel truth, Democus's troubles were greater after the storm than before. That day of foreclosure would surely come. O Democus, on that day must you change your name and shave your whiskers? Lacking foresight, will Republicus "Democus" Americus be prepared for the foreclosure? Very truly yours, James R. Carr |

Though he had already had military

training, and had been called by the draft board to go up to St. Louis for a

physical, which he passed, he was never drafted during the war. This may have

been merely the luck of the draw, or it might have been because of the shadows

of doubt that had been cast upon his national loyalty. More likely, he simply

enjoyed an exemption due to his defense-related work at the Ordnance Plant.

Of course, there was never any real doubt as to his loyalty,

in spite of his difference of opinion on war policy, and he certainly wouldn't

have been hired at the Ordnance Plant had the government determined that he was

disloyal, or in the least a security risk. Security risks are not hired at bomb

factories. (At least we hope not!) Still, he often had the feeling that he was

being singled out and "watched." When the brass came to inspect the

Ordinance Plant, he felt that certain ones of them eyed him particularly

closely. When president Truman later came to Harrisburg after the war, he

believed the Secret Service had him under close surveillance.

Even long after the war, it seemed to him that unknown

"organizations" were actively working against him. His mail often

seemed to be interrupted, or appeared to have been opened. His mail orders

seemed to be unduly delayed or failed to show up at all. As a consequence his

paranoia was reinforced.

He didn't know about the government agents sowing

suspicion against him until many years later. He felt the Catholics were out to

do him damage. The only reason he might have suspected the Catholics was perhaps

that his sister Flo's husband was a Catholic, and perhaps they had had a falling

out. This paranoia lasted for many years after the war. While he was in

Michigan, he always insisted that some "organizations," were spending

a lot of time meddling in his business. I didn't believe it at the time, but he

may have been right. War hysteria and paranoia of a nation can do strange things

to people. I didn't know about his letters to the editor at the time, as he

never mentioned them to me until years later.

It was over thirty years later that his "best"

pre-war friend (Clarence Santy), finally admitted that he had been

questioned about him in Harrisburg by the FBI, or other government agents. If

his best friend wouldn't tell him, then who would? Who else had the government

agents spoken to, planting the seeds of doubt as to national loyalty? What

organizations, through such people, had been alerted that James Carr was

"suspect"? Perhaps we will never know. But even his Uncle Bill,

possessed by "war fever," had suspected him of being a German spy —

a member of the infamous "fifth column" — because of his outspoken

criticism of FDR, the war, and the British.

Though James was little inclined to join any formal

organizations, particularly anything like a church, he did come to identify with

the Unitarian church. For some time in the 1950s he was a member of the

Unitarian Church of the Larger Fellowship, which was basically their

"mail" church. His "ideology" parted company with the

Unitarians, however, when it became apparent that the Unitarian Church was

"full of bleeding heart liberals during the Civil Rights era." He

disowned the church.

In an earlier era, James had been an unabashed open-minded

progressive. But as the nation was transformed by such things as the Second

World War, Korea, Vietnam, Civil Rights, and the counter-cultural movement, he

effectively became a social conservative in spite of himself. But he hadn't

changed any. The nation was changing around him and the culture was being turned

inside out.

Somewhere along the line he taught himself to play

chess, and during the years at the Ordinance plant he took on all comers. He

studied the games of the masters, such as Laskar, Morphy, and many others. He'd

travel fifty miles for a good game, and he delighted in beating the "more

learned than thou" class of players who often challenged him and regretted

it. More often, he went out of his way to seek them out and challenge them. This

included the head of the Southern Illinois University chess club and other

professors at Carbondale. He was nearly unassailable. If not actually a chess

master, he was an expert that few short of masters could handle.

|

James very single-handedly built a

beautiful little home next door to his brother George, south of Rudement. His

ability as an architectural draftsman was on a professional level, but he never

had any desire to do that kind of work professionally. Several in the area of

his home had him draw their house floor plans for their dwellings.

This is the house that James built on weekends during WWII. This photo was taken about 1955, after it was sold and painted white. Wife. Mildred, choose the house design from a Sears Home catalog, and James drew the plans from that illustration, but he designed and built the interior according to his own tastes. |

It was a one man job, and the digging in hard clay soil was all shovel work. Note the ditch. |

|

|

|

|

|

When the great war was over, James found

that the pulp writers' market did not revive. Making a living in the country in

those days was not all that easy. The depression never seemed to leave Southern

Illinois. If one was not a farmer or a coal miner, or the son of a local

merchant, there was little hope of finding a good job around Harrisburg. The

pre-war WPA projects, along with the writers' and arts projects were history, as

was the Ordnance Plant.

All the good employment breaks that did open up were for the

returned war heroes. George came home and was hired by the Rural Electric Co-Op.

Later, he was offered the job of manual arts teacher at the Harrisburg

junior-high school, and allowed to gain his teaching credentials over a period

of time. No such jobs were in the offing for the non-veteran, politically

incorrect, James.

The post-war boom bypassed Southern Illinois, and work

was scarce, but James tried to make it in the area he seemed to love. He loved

home and always gravitated to "family" in spite of his peculiar

"love-hate" relationship with it.

Uncle Bill had long been a mechanic, and had built a

shop near the highway at the old home-place. James purchased a welding machine

and taught himself to be a welder, and opened a welding business in the shop.

With his new self-taught skill as a welder, he made a cement

block machine and went into the business of making cement blocks in addition to

welding. Though the machine made the actual blocks, all the related work

involved was of the back-breaking variety. Hauling water (all water had to be

hauled from the creek or drawn by hand from the well some distance away at the

house), handling bags of cement, mixing it by hand in a mortar box, and stacking

and restacking blocks were unending chores, but his blocks sold well.

|

|

|

He also taught himself to be a professional locksmith.

Divorced, he soon had to sell the home he had built for his wife, Mildred, in

order to settle the divorce ruling and get a stake. He purchased a lot at

Morro Bay, California, by mail-order, site-unseen from a magazine ad. Then he

sold his block machine (#1), and made a brief sojourn to California just prior

to the Korean War. He found his $99.00 well spent (much to the

disappointment of "friends" back home [who figured he'd bought a lot

in the Pacific Ocean], and the dismay of real estate men around Morro Bay), and

he opened a locksmith shop in the town of Morro Bay.

|

|

|

|

When the Korean conflict broke out,

however, he returned home and resumed welding. He built a second and improved

cement block machine, but never put it to the test. Perhaps he'd got a whiff of

salt air at Morro Bay, and it set him to thinking of building a sailboat and

sailing to the South Seas where, as he said, "people were still

civilized."

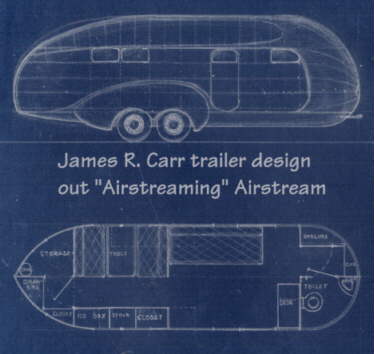

James then set to building himself a house trailer

which, when finished, was better looking than any at that time commercially on

the market. He dubbed it the "Nomad" and in 1952 departed for Michigan

where he hoped to get a good job and build his boat while near his son, Bill,

(me—ten years old at the time) who was by then in Michigan with his mother and

step-father. He landed a good job as a welder on the Pontiac Grand Trunk

railroad rip-track, and began working toward the goal of building a boat. For

three years he lived in his 11-1/2 foot "Nomad," in trailer

parks, often staving off eager would-be purchasers. He finally purchased a

two-acre piece of land near Clarkston, Michigan with a basement house, and a

barn. The barn was soon turned into a workshop and he started buying the tools

he'd need for building a boat.

|

| One of several designs that he couldn't afford to build. He built the one pictured below instead. |

|

|

|

|

Unfortunately, a layoff at the rip-track shattered all his boat building plans, and in the end he had to abandon his boat dream, and property, and head back to the farm in 1959. He'd hoped to get a job as a welder on the Harrisburg rip-track, but, at 48, he was told he was too old. (Later, when the law was changed, they came to him and tried to hire him. But by then it was too late, he had built a new shop and was again in business for himself.)

Raymond Turner, an old neighbor from Rudement, was the blacksmith who worked with my father at the Grand Trunk Railroad in Pontiac. My dad took me to the rip track a couple of times, and introduced me to all his bosses and co-workers. I was 13 years old in 1955. The blacksmith shop was where most of the welders and "car knockers" gathered for lunch and other breaks and played checkers. I think it was about 1955 or 1956 when my dad was laid off -- when he finally got his "union seniority." That was ironic, and I never understood it at the time, and I guess my dad hadn't understood it either.

He thought getting his seniority would mean his job would be more secure. But he related telling the boss, "Well, Mr. Sherman, I guess you notice I've finally got my seniority?" To his astonishment, Mr. Sherman didn't seem please, and said, "Yea, and now I'll have to lay you off!" Until he attained his "seniority" status (that is, I guess, full union membership), they could keep him on as a welder, protected, apparently, as a union applicant. But when he got his "seniority" a union man with greater seniority could bump him, and he was immediately bumped.

The lay off was temporary, and he was finally called back about two or three years later. But by then he'd already given up the place he'd bought in Michigan, and returned home. When he got home, he applied as a welder at the Big Four rip track at Harrisburg. They needed a welder, and actually wanted to hire him, but company policy at the time stipulated no new hires over 40. He was about 45 then. A few years later, when age discrimination had been addressed by federal law, they actually contacted him and tried to hire him. But by then he'd already built himself a welding shop and declined the job. Though he made very little money at his shop, he liked being his own boss too much to go back to a regular, even "good paying," job. He survived, hand to mouth, running his own shop in the country, until he could "retire" and collect his minimal Social Security and his "supplement." It wasn't much, but he felt richer than he'd ever been in his life, and lived happily for the next 30 years as a retired "country gentleman" in his shop.

James built a new shop of cement blocks, using lumber from

the old frame shop (which had originally been uncle Bill's mechanic shop but

which the new owners wanted torn down), for the roof and gables, and resumed

welding to make a living. Besides being a welding and woodworking shop, it was

equipped as a blacksmith shop, complete with an ancient 250 lb. anvil, a forge

he made, and hand-made blacksmith tools he'd bought from a retired local

blacksmith, though they were only used as an auxiliary to the welding business.

Though his business was basically welding and woodworking, he named his

establishment, "Ye Olde Shawnee Hills Forge."

For all that, business being very slow, he took a job in St.

Louis for a year or so as a live-in custodian at the Veil Prophets Den. Due to

economic necessity, the boat dream was replaced by the idea of making Eli Terry

pillar and scroll clock reproductions. When he returned from St. Louis, he

started making clocks. He made 17 clocks before other events intervened to

disrupt his plans.

|

|

It was during the period of living in this

shop that Saturday nights developed into "Chess Nights." Sometimes

checkers or poker were played, but it was chess that James always preferred. The

shop became a gathering place for a strange assortment of local people -- from

"redneck" friends and neighbors, who came for beer and maybe a game of

poker, to some of the future literati and notables of the area who were

interested in "getting their minds opened" along with some good

entertainment. Usually there was guitar playing and singing at the

get-togethers. And sometimes he could be persuaded to break out the accordion

he'd taught himself to play. Among the attendees numbered future writers, poets,

other professionals, and at least one future judge.

|

|

The shop that James built in 1962 was

situated on a piece of real estate that was owned my his mother (another piece

of ground from uncle Bill's farm). It was next door to the house he had built

and sold, and between it and the old log farmhouse we called the family

homestead. His mother had so arranged it that it would go to her three children,

James, George, and Flo, upon her death. But when she had to be committed to a

nursing home, the state had a claim on the property. The old family homestead

had been sold upon Uncle Bill's death in 1961.

Threatened with the possible loss of the property, and

eviction when his mother died, James set out, in the late 60's, to find property

perhaps he and his son, who was then in the merchant marine, could purchase for

a new home base. In 1967 he found "the perfect farm" and Bill bought

it. This was the old Luther Edwards farm, three miles south, on Possum Ridge, in

Pope County.

In 1970 James started building a second shop on the new

homestead. There he continued to operate his welding shop, but never got back to

making clocks. He continued reading, and playing chess. "Chess Nights"

continued, and the unlikely mix of chess players and on-lookers continued. They

assembled there either to play or simply drink beer and partake of the company

of one of the area's most unusual "characters."

The place was a favorite meeting spot for many years. In

addition to beer and liquor, there was James' famous popcorn that we all loved.

He'd pop a large dishpan full of it, and announce, "Eat 'til you bust, and

if that isn't enough, there's more where it came from." The secret

ingredients were (1) pop the corn in spicy sausage grease and (2), salt it

liberally with plenty of garlic salt.

Neighbors, hippies, bums, teachers, and chess challengers

from other parts of the state often appeared. There were "regulars"

who came every Saturday for years on end, and many others who just dropped

in from time to time. The place almost became famous, and probably would have

except that James didn't want too many strangers. He nixed the

opportunity of being featured on Paducah channel 6 nightly news. He got more

public exposure than he wanted when the late Joe Aaron, a columnist for the Evansville

Courier, did a surprise article on him after a visit. Entitled Thoreau's

'Walden' revisited: James Carr on Possum Ridge, the article was

reprinted as The Clockmaker of Possum Ridge,

in Aaron's 1983 book "Just 100 Miles From Home".

|

|

While James made an extensive study of chess

throughout his adult life, he was also quite interested in the game of poker,

and studied it extensively in spite of the fact that he seldom played in a

serious way. He used to play poker more frequently in the old shop than in later

years in the new ship, since many of his friends at the time were chess

illiterate and had no desire to learn the game. Because James and the company he

kept were poor, the games were always penny ante, with a nickel or dime limit. I

almost got poker fever back in those days myself, as I picked up a few pointers

from my old Pappy. But the problem with poker among friends, of course, is that

the fun of playing well and winning more often than losing, was always

considerably diminished by the fact that it wasn't fun to take money from

friends you knew where as poor or poorer than you – and this is why James

never became a poker enthusiast to the extent of his actual interest in, and

natural affection for, the game.

James' favorite poker book was The Education of a Poker

Player, by Herbert O. Yardley, published in the 50's. I call it my old

Pappy's Poker Bible. Over the years he spend considerable time making it a very

comprehensive poker manual, by pasting clippings of excerpts from other poker

books in all the blanks spaces on the pages throughout the book. Included in

these additions, among many other clippings, were most of the text and quaint

illustrations from Poker according to Maverick, as nice little

book published in 1959 by Warner Bros. Pictures, Inc. – a book supposedly

written by Bret Maverick himself, (a fictitious character played by James Garner

in the popular TV series – actual authorship is not given).

One reason James liked Yardley's book so much was that it

contained a lot more information than on poker alone. It was one of the first

reliable published sources that revealed Franklin D. Roosevelt's foreknowledge

of the attack on Pearl Harbor that facilitated our entry into World War Two.

Yardley was a life-long poker enthusiast who became one of the nation's preeminent

military code breakers. He helped crack the Japanese military code and was in

China, on loan to Chiang Kai Shek, during the period just prior to Pearl Harbor.

The story of his experience as a military intelligence "insider" at

that time is woven into his book on poker. This confirmed things that James had

already suspected about Roosevelt and our entry into World War Two. His Yardley

book also contains several newspaper and magazine clippings on the same

subject.

James' business philosophy had little to do

with making money. His business plan was to never make enough money to have to

file income taxes, and he never had to. His mode of doing business discouraged

all but the most determined customers. He'd do the work if they didn't mind

leaving it for a week or two — until he "could get to it." Likely he

was in the middle of a new book, or just re-reading an old one. The only

exception was when local farmers (and fortuitously there weren't too many of

them), came in with broken equipment during harvest or mowing season. Then he'd

do his best to get the job done so they could get back to work. He notoriously

under-charged for his work, and sometimes didn't charge at all. If the

"customer" was able to weld, he'd be invited to do the work himself at

no charge, or only enough to replace welding rods or gas.

Neighbor Alfred Wasson knocked down James' welding sign one

day while bush hogging near the highway in the Summer of 1973. He went up to the

shop to report the accident, assuring James that he'd put it back up. James

said, "That won't be necessary Alfred. You've done me a favor and saved me

the trouble of taking it down myself. I'll be 62 years old in a few months and

I've been thinking of retiring anyway. I think I'll just retire early."

And he did — and when he finally started getting his small

Social Security and Supplement checks, it made him wealthier in money than he'd

ever been during his working career. He said it was just like having a couple

hundred thousand dollars in the bank and living off the interest. He retired to

doing just what he had been doing all along. Reading, playing chess, drinking

beer and whiskey (usually supplied by visitors), and just enjoying life in the

modest way few men are ever rich enough to do. Oh, he would still do occasional

welding work — but, unless it was an emergency, the customer had to be pretty

determined.

For all his shortcomings, I wouldn't have traded him for any

other father. I only wish I'd had the capacity to learn all the knowledge he had

to impart. Oh, his shortcomings were considerable, at least in the opinion of

many, but even one of his most ardent detractors (his sister-in-law, Gertrude

Carr), once admitted "James is probably the best-read man I've ever

known."

His knowledge of literature, philosophy, and an array of

practical subjects was truly prolific. His memory was photographic. But he

tended to be somewhat "impractical" by popular standards. He had a

great lack of ambition and drive to make money. He would not compromise his

principles in the name of the quest for monetary reward. And that was why many

would consider his life a a waste and a failure. An extraordinary person with

many talents and great potential, who absolutely refused to put his assets to

what might be called practical use.

James Carr was self-taught in many fields and trades. He was

an artist, an architect, a cabinet maker, a master carpenter, a locksmith, a

welder, and (among other things), a damned good chess player. He could strum the

guitar and play the accordion, though he was never what might be called an

accomplished musician. He refused to be a jack of all trades and master of none.

If he decided to learn something, he became an expert on the subject, through

reading, before turning his hand to it. This perfectionism, of course, was

perhaps one of his greatest nemesis. It prevented him from doing many things

that he might have done, could have done, and maybe should have done. But he

refused to do anything unless he could do it right, and do it right the first

time. "Good enough," was not his way. He wanted near perfection, at

least as he saw it, and he had a demanding artist's eye.

I learned a lot from my "Old Pappy." He

taught me to be a skeptic early, and that men thought, and thought rather well,

even long before the Christian era. He introduced me to the great thinkers of

ancient Greece and the generations of philosophers that followed. He introduced

me to good literature, so I was never overly impressed by "pop

culture." He taught me to weld, do woodwork, and even the rudiments of

marine navigation.

He broadened my horizons, and inspired my interest in the

world about us — and my interest in the sea, sailing, and ships. I learned

from him that other cultures stood beside, and not necessarily beneath, our own

— even that the Japanese and Germans were human too, in spite of the recent

great war. He had taught me to play the guitar. He could always pick up the

guitar and play a few old songs which were his favorites, such as the

"Strawberry Roan" and "Abdullah Bulbul Amir." Though he

loved good music as he loved good literature, he wasn't particularly fond of

classical music. He preferred that brand of popular music that becomes

considered timeless classics — such as "Girl of my Dreams,"

"Danny Boy," "Indian Summer," etc. He also liked Straus

Waltzes, and he liked lively Polkas played on the accordion.

My dad refused to buy a television set. He considered them

abominations. But finally a neighbor gave him one (in about 1965), and he felt

he couldn't insult him by turning it down. Once he got it, of course, he watched

it and became a Lawrence Welk fan. He preferred talk radio to TV. But he always

preferred reading to either, though he often listened to radio while reading.

|

|

My dad was an

Iconoclast. His heroes were not pop-heroes. Nor were they the political heroes

most people admired. Neither Abraham Lincoln, nor Franklin D. Roosevelt were

heroes in his book (though he had been an early FDR supporter, and could still

recite the Gettysburg Address at age 89). Those two presidents, along with

Woodrow Wilson, he said, had managed to get more Americans killed than any

others — and that (as has so often been the case throughout history), was

their primary claim to undying greatness. Though a life-long Democrat, he didn't

think much of Lyndon Johnson and his Vietnam War policy. In his opinion, LBJ was

another democratic president aspiring to fame by getting as many young American

men killed as possible.

Two things come to mind when I think of my dad and the

Vietnam War era. I'll never forget him toasting one of his nephew's 18th

birthday.

"Freddy," he said, "Tomorrow you'll be old enough to be drafted into the Army and sent over to Vietnam to get your head shot off."

"And, just think," he continued, after a pause — raising his beer in salute to young Freddy, "In just three more years, you'll be old enough to drink one of these beers."

The other was once when I

heard my dad ranting angrily in the shop. I thought he must be having a terrible

argument with somebody and I hastened in to see who it might be. I found him

sitting in front of his little radio listening intently to president Johnson

giving a speech. As LBJ spoke to the nation, my dad was giving him a piece of

his mind.

His heroes were history's greatest thinkers — the

philosophers and great writers and poets. His favorite philosophers were perhaps

Voltaire and Nietzsche. Two of his favorite poems were John Greenleaf Whittier's

"Snow-Bound," and Edward Fitzgerald's "Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam."

At one point in his life he was able to recite all 101 stanzas of the Rubaiyat

— an amazing feat. And, of course, he had to plant some chestnut trees around

the shop because of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's "The Village

Blacksmith" — "Under a spreading chestnut-tree, the village smithy

stands..."

My father did have his strong prejudices. While he admired

the Japanese and Chinese cultures and marveled at the civilization that produced

Ankor Wat, he saw the world through the prism of the Victorian white man's

traditional perspective. He was a strict idealist unwilling to accept and cope

with a flawed world and society. He was a Victorian idealist in a decadent

world. He was a Puritan idealist, in the unlikely body of an agnostic.

Thus, he was stymied wherever he turned and had withdrawn

from society into his own world. The shop and good literature were at the center

of that world. His vast knowledge of literature and philosophy were perhaps

wasted — used only for his own pleasure and thought processes. "He could

imitate Irving, play poker and pool, and strum on the Spanish guitar." He

could do so many things, but he became more of a hermit than anything else,

doing very little, and that isn't considered success in this world.

In spite of that, however, he had a positive impact on

many lives, and in this he was far from being a failure. He opened many minds.

He taught many to think, free from the narrow constraints of such things as

orthodox religion, conventional wisdom, and what has become known as

"political correctness." Those who admit to being positively

influenced by him include writer-publisher, Gary DeNeal, Native American poet

Barney Bush, and Judge David Nelson, to mention only three besides myself.

James lived at his "new" shop on Possum Ridge for

over twenty years, from 1971 to 1995. An old bachelor, without plumbing — no

running water, and no bathroom. He fried cornbread, ate a lot of garlic, and was

always in the best of health. He heated with coal in an old pot-bellied army

stove, later replaced by a new pot-bellied stove he named "Rhino."

He gardened for several years. He had liked guns as a young

man, and that interest was rekindled in his old age. He became interested in

hand-loading ammunition, and that was one of his major hobbies during his last

years at the shop. And chess night gatherings were always the highlight of the

week. Mail-time was the highlight of each week day, as he was a prolific

letter-writer, corresponding with me, when I was away at sea, and several

pen-pals for many years.

And he continued to read prolifically on an array of subjects

from hand-loading to history and philosophy. He had always loved poetry, and all

nature of fine literature. His literary interests ran from Washington Irving's

works to the Santa Fe Trail and Revolutionary and Civil War history. He studied

about lost pirate treasure, sunken Spanish galleons, and the treasures of the

Sierra Madre. He bought several metal detectors, and would often search for

hidden treasure around the shop.

END OF AN ERA

Catastrophe struck on Saturday, the 4th of

February, 1995. The chess crew had left, and my dad and I were having a final

beer before calling it a night. He stood up from his old captain's chair, lost

his balance, and fell against old Rhino, the pot-bellied stove. His upper leg

was broken just below the hip socket.

An era had ended. As is so often the case at such age, he

wasn't able to rebound and resume his traditional self-reliant life in the shop.

The trauma of the hospital, the operation, and brief stay in a nursing home, was

too much for him to handle. Though he recovered physically to a great extent, he

was never able to recover psychologically from the accident that, for the first

time, at age 82, had brought him face to face with the infirmities of old age.

Because of the lack of running water and bathing facilities,

among other things, returning to the shop was out of the question. He lived in a

mobile home on the property, and though he entertained hopes of returning to the

shop for some time, it eventually became apparent that it was not to be.

An attempt was made to resume Chess Nights at the trailer,

but the spark was gone. James failed to recover his old conversational fire. And

nobody liked the trailer. Even more importantly, James had completely lost his

interest in the game of chess. He refused to participate or even watch. Much to

the disappointment of all, he remained glued to the TV instead.

The chess gatherings thus came to an end forever. Though he

recovered physically, he quickly fell into a syndrome of dependence, and never

asserted a determination to fully recover his self-reliance. He refused to use a

cane, preferring the security of a walker. He became dependent on a government

subsidized house-keeper and cook who visited daily. He never again attempted to

cook for himself. His cornbread and beans were no more.

His short-term memory began to fail him. He often became

confused, and forgot even the most familiar names. Yet, in many ways he was

still very much himself. Though he never regained his ability to type, mail-time

continued to be the highlight of every day for a long time. He'd hobble out to

the mailbox as best he could with his walker. He ordered books and other items

through the mail. And he subscribed to his favorite magazines, such as,

"Guns & Ammo," the "Southern Partisan,"

"Harper's," and "Atlantic Monthly," etc. And he ordered good

books even though he could no longer read them.

He got the latest edition of the New Columbia one volume

encyclopedia, the one volume compressed edition of the Oxford English Dictionary

(which requires a strong magnifying glass to read), the two volume Short Edition

of the same dictionary, Merriam Webster's Encyclopedia of Literature, to mention

only a few. And... and he waited expectantly for the promised ten million

dollars from Publisher's Clearing House.

Then came the day that he fell down out near the mailbox and

couldn't get up. A passing trucker saw him and came back to help him to his

feet. His last outside activity thus came to an end.

Still, he exercised many of his old interests. He still

admired his rifles, and acquired a model car collection. He finally bought a

model Spanish Conquistador-type helmet and a Concord stagecoach — two items he

had always wanted. And he quested after the allusive "Bayo" bean. And

his love for beer and whiskey continued, but he now had to be held to a modest

and strict ration.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Aside from myself and my two children, there was one other person who looked to my dad as a father figure. This was my dad's nephew, Harry Witt. Cousin Harry had grown up visiting often with my dad, and often spending weekends with him. Harry lived in town and visiting "uncle James" in the country was always a special treat for him. Harry's own father had passed away when he was a baby, and my dad had filled a void in his life for which he has always been grateful, and has always gone out of his way to show it. And I know my dad cared a lot for Harry as well.

Harry moved to New Orleans after he got out of school, but he made the sojourn up to Southern Illinois to see James and his other friends just about once a year, usually in May. He'd always have a big party at the shop while in the area, usually bringing a large mess of fresh oysters, shrimp, or crawfish. And, of course, plenty of beer. There would be a crowd of Harry's friends, most of whom had become longtime friends of my dad through him. And there would be my dad's "chess" friends and neighbors.

It was Harry that threw my dad's last real party on the occasion of his 90th birthday, on October 29th, 2002. Harry and his fiancé, Jeanne, came up from Louisiana special for the occasion, and brought all the trimmings, including a bushel of crawdads and a birthday cake. Several of Harry's and my dad's friends showed up, and we all had a grand party with a large fire in the back yard. There was plenty of guitar picking and singing, and my dad even picked up a guitar and strummed it a little.

It was the last time my dad was allowed his fill of both beer and whiskey. He took full advantage of it, and enjoyed himself tremendously. At one point, having partaken of sufficient drink, he forgot that he couldn't walk and got up out of his chair to take a walk. He fell straight forward, almost toward the middle of the fire in front of him.

Nobody was quick enough to catch him, but he had enough presence of mind to twist himself enough to barely miss the hot coals, and roll away from them as he landed. Fortunately, he wasn't hurt.

He laughed an embarrassed laugh, was helped up and back into his chair, and announced that he thought he needed another drink after that. He wasn't drunk. He almost never got that way (and never the sloppy falling down kind), in his 90 years of being a dedicated drinking man. But he had become pretty forgetful.

It was my father's grand finale, for by his 91st birthday he would be unable to enjoy such a party. I'll forever be grateful to Harry for making that last big shindig for my dad happen as it did. It was priceless!On the 5th of June, 2003, that most dreaded time finally arrived when my dad could no longer live alone even with frequent daytime companions which included his grandson, Jim. He often fell when unattended, and was usually unable to get up. The move was effectively forced by his doctor and the home care services people who determined that he needed twenty-four hour care. He became a resident of a nursing facility in Golconda, Illinois.

When that heart rending time came, he didn't complain, but accepted the inevitable — which, of course, wasn't him at all — and that was the sign that he really needed to be in a nursing home. He increasingly had trouble articulating the simplest ideas or remembering words he wanted to use, and he would become highly annoyed at himself because of it. He had often called it "Old timer's disease."

In spite of his increasing infirmities of mind and body, his old self sparkled through frequently enough while at the nursing home. He was down for the count, but not yet out. A lion's heart still beat strongly in his breast. When I'd ask whether he wanted anything from the shop (he'd forgotten about his six years at the trailer), he always declared that he didn't, saying he'd be "getting out of here in a day or two."

He had a copy of the "Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam" that a visitor had kindly printed out for him. It included the note, "Thank you for enlightening me!" which goes to show that my dad hadn't forgotten all, and still endeavored to open peoples' minds, when they would listen.

This does not come close to telling the whole story of my father's life. It doesn't really do him the justice that I would have liked, but it does show that there was much more to the man than many have imagined. He may have been under-appreciated by those who didn't really know him, but he is very much appreciated and loved by a few, and me most particularly.

LAST RITES

At 5:29 A.M. on the 10th day of August, 2004,

about fourteen months after taking up residence at the Golconda nursing home,

James Robert Carr passed away quietly at the hospital in Rosiclare, Illinois. It

was about two weeks after he had been admitted for a nagging and recurring case

of pneumonia. He was just over two months shy of his 92nd birthday.

He was buried beside his beloved mother Sybil (Gurley) Erwin

at the Bolton Trammel cemetery in Stonefort, Illinois, at 6:00 P.M. on Thursday,

the 12th of August. The burial was well attended by many friends and few

remaining relatives who live in the area. An Eulogy was read by his grandson,

James Roy Carr. His friend and neighbor, Ray Wallace, offered a prayer.

He is survived by his half brother and sister, Joseph Potts

and Rachel Witt and their children and grandchildren; myself (his son); his

grandson, James Roy Carr; granddaughter, Lilia Thi Carr; and great

granddaughter, Chloerisa James Carr; and a cousin, Joan (Gurley) Dickerson.

Though I was not present at the time of his death, nor at the

burial, I had been there with him when he passed from consciousness and sporadic

lucidity into a comatose state from which he never recovered. I could see that

his time was short when I visited on Tuesday the 27th of July, but on that day I

didn't realize how short. In fact that was the last time that we actually

communicated and it was all too brief.

Just before he left us, his old spirit

shined through for a moment (at the hospital where he spent his last days), when

I reminded him of the good times he and I had had together. His eyes shined and

he perked up as I mentioned the chess nights so many of us had enjoyed with him.

"Yes," he said, "we did have some good times."

Then I suggested that all he probably

needed to cure his present condition was a "few beers and a shot or two of

whiskey." He smiled and his eyes sparkled momentarily. He said, "That

just might do it." But that was the last time he addressed me and the last

time I saw him smile and saw a twinkle in his eye. Then he lapsed into a

semi-conscious state and cried for "help," as he had done several

times previously that day. But he was unable to tell anybody what kind of help

he needed.

He needed to pass on – to be released

from this earthly life – I later realized. The next time I saw him, he had

managed to do that. Though he was still breathing, and his lion-sized heart was

still beating weakly in his breast, he had been released from his pain and

suffering. Then he passed on, without regrets for a life well spent in his

singular way of thinking. (from his eulogy)

After that last time he spoke to me, he only cried out once

for help, and then seemed to drop off into a quiet sleep. My son, Jim, had

joined us just in time to hear his last words with me. We then left him to his

repose, not suspecting that he had spoken his last words to anybody. I told

myself that the next time I visited him I'd tell him how I have always loved

him, and that he was free to go — that we'd be together again one day.

But the next time I visited him he was already gone. Though

his body still lived, his eyes were vacant and he gave no sign of hearing. He

had slipped away quietly into another world. Too late, I grasped his bony old

shoulders and told him that I loved him and that he was free to go. Though I

said good-bye, he was beyond hearing.

Though I had missed my last chance to express my love and say

good-bye while he was still able to hear, I guess it was fitting that the last

words he heard from me were somewhat flippant in nature. He had always loved

beer, whiskey, and good companionship, and had hated good-byes.

While he was still thus on his death bed, I had to leave home

(as I had done so many times before), to resume my employment and rejoin a ship

in Los Angeles that would not wait.

Deciding to leave and rejoin my ship at that time was a

difficult and heart-rending decision, but we had already come as close to saying

a final good-bye as he would allow. I knew I could be of no further comfort to

him. The time for that had passed, and I had a feeling of great loss and of a

profound loss of opportunity. As much as I had always loved my father, I had

never actually said it to him in so many words. Now I never could.

He lingered five days after my departure, as if he had waited

until I was safely aboard my ship. I was at sea in the Pacific at the time of

his final passing and burial.

William R. Carr

Aboard the M/V Sealand Patriot

Bering Sea, enroute to Yokohama, Japan

Monday 16 August, 2004

|

Your are visitor number

since

6 February, 2004. Thanks for visiting.