The American People’s Money

by Hon. Ignatius Donnelly

Chapter II

THE SECOND DAY.

“ Good morning, Mr. Hutchinson,” said the farmer, “ I hope you had a good night’s rest and enjoyed your breakfast.”

“ Yes ; the air seems to improve as we go west.”

“ We are rising gradually onto the table-land of the continent. We are getting into the great breathing spaces. Henry Ward Beecher, the first time he inhaled this kind of air, drew a long breath and said,—‘ Ah ! this is beefsteak !’ He was right. The animal organism is fed as much by the air as it is by the earth ; but some atmospheres are more nourishing than others, even as some earths are. Lord Bacon wrote, at one time,—‘ I live upon the swordpoint of a sharp air.’ And how beautifull is Banquo’s picture :

‘ This guest of summer,

The temple-haunting martlet, does approve,

By his loved mansionry that the heaven’s breath

Smells wooingly here ; no julty, frieze,

Buttress nor coign of vantage, but this bird

Hath made his pendant bed and procreant cradle :

Where they most breed and haunt, I have observed

The air is delicate.’

“ This intercontinental table-land of America, lying higher up, near the clouds, surcharged with electricity and fed by the most exquisite parts of the atmosphere, will produce the grandest race of men and women that has ever inhabited the planet. They will be the masters of the continent, if not of the world. Observe the height, vigor, activity and breadth between the ears and eyes of the new generation that is springing up,—they are extraordinary.”

“ Then you don’t think the Plutocracy is going to enslave them ? You were very pessimistic last night,” said Mr. Hutchinson, sarcastically.

“ No ; they will do their best. But the human family having once risen out of serfdom cannot be forced back into it. There will be struggles and conflicts, perhaps revolutions and wars ; sometimes the people will be prostrate upon their backs, chained hand and foot ; and again they will be up with flashing and unobscured eyes, striking right and left, like a thresher with his flail. The contest may terminate in a few years, or it may run through centuries ; but ‘ there is a power in nature which makes for goodness, and evil is not to be our god. The Everlasting Justice will not permit the millions to starve that the thousands may be overwhelmed with hog-like superfluity.”

“ No ; they will do their best. But the human family having once risen out of serfdom cannot be forced back into it. There will be struggles and conflicts, perhaps revolutions and wars ; sometimes the people will be prostrate upon their backs, chained hand and foot ; and again they will be up with flashing and unobscured eyes, striking right and left, like a thresher with his flail. The contest may terminate in a few years, or it may run through centuries ; but ‘ there is a power in nature which makes for goodness, and evil is not to be our god. The Everlasting Justice will not permit the millions to starve that the thousands may be overwhelmed with hog-like superfluity.”

“ Let us avoid generalizations,” said the banker, “ and come down to practical details. You said last night that the evils which men endure are due to misgovernment. What proof have you of the truth of that statement ?”

Compare Ireland and New Hampshire. The former is one of the richest bodies of land on earth ; fed by the showers of the gulf stream ; indeed an emerald land for ever green ; where the temperature rarely goes below the freezing point or rises to tropical heat ; a land known to the ancients as a region where two crops could be raised in the same year. And yet what is it ? A land of beggars, where the population has fallen off one-half in fifty years, while everywhere else on earth it is increasing. Why ? Because of misgovernment. The country has been in the hands of plunderers, and has been governed in their interest, not in the interest of the producing classes of the island. The people are merely instruments to turn the fatness of the land into money for the idlers. Parnell said you could travel for twenty miles, in parts of Ireland, without seeing a human being. Redpath said that there were no dogs in large sections of that unhappy land because the wretched people could not spare the food to sustain a dog !

“ Then, turn and look at New Hampshire ! Masses of barren mountains where a hungry eagle would starve to death ; the soil producing an annual crop of stones sufficient to fence it into five-acre lots, with enough to spare on every thousand acres to build a city. The farmers it is said sharpen the noses of their sheep to enable them to reach in between the stones for the scattered blades of grass. And yet New Hampshire is a land of prosperity, a land of culture, a land of wealth, a land of millionaires. I came from there. You will hear the piano playing in mansions beside rocky roads where there is scarcely room to turn a wagon ; while the railway cars are packed with an endless concourse of bright, handsome, intelligent people, perpetually moving to and fro in search of business or pleasure.

“ Why the difference ? It is simply because New Hampshire has not been governed by non-residents or idlers, but by her own people. They have taken advantage of every opportunity ; they have developed every resource ; and they have reached out and gathered in the spoil of distant and more favored regions.”

“ But is not religion responsible for this difference between Ireland and New Hampshire ? The Irish are mostly Catholics.”

“ I know,” said Mr. Sanders, “ that that argument is often used ; but if you will stop and think for a moment the Belgians are as Catholic as the Irish, and they are the most industrious and prosperous race of toilers in Europe. Next to them come the French peasants, dwelling on their one acre and five acre farms, given them by the great revolution, and cultivating them to the highest pitch of perfection. They are all Catholics ; and in the midst of even these disastrous times France is flourishing. Catholic Austria is no whit inferior to Protestant Prussia in industry or economy. Indeed, how is it possible that a man’s belief as to the presence or non-presence of God in the sacrificial wafer can affect the quantity of meal in his flour-barrel or the thickness of the coat on his back ? ”

“ But their race may account for it,” said Mr, Hutchinson, “ the Irish are Celts.”

“ So are the Welsh and the French and the Belgians and the Highland Scotch. The Irish of to-day are the most composite race in the world. Before the discovery of America Ireland was the most western land of Europe, where all the converging lines of migration met, as they are meeting to-day in these United States. Phœnicia, Greece, Italy, Spain contributed to the original stock. One sixth of the Irish words are Basque. All the coast towns of Ireland : Dublin, Cork, Drogheda, Waterford, etc., were settled by the Danes, Swedes and Norwegians. Dublin was a Norwegian city for four hundred years and nothing spoken in it but the tongue of the Northmen. The Scandinavians held possession of the island for generations ; and a Gothic soldier was in every Irish house. No, sir ; the cry of race is the excuse for injustice. It is amusing to hear a little, swarthy, black-eyed

Englishman, with all the insignia of Celtic-Briton blood, trying to prove that a raw-boned, six-foot, red-headed, fair-skinned, blue-eyed Irishman, with Goth written all over him, is unfit for anything but poverty and oppression-because he is a Celt !

“ No, sir,” continued Mr. Sanders, “ the difference between Ireland and New Hampshire represents the difference between good government and bad government. The statute-book is at the bottom of everything. Ireland is naturally rich—and a land of paupers. New Hampshire, like Eden after the Fall, is a place of stones and thistles, but she is the home of gentlemen and princes. The time was when we Americans, filled with our inherited English prejudices, mocked the poor Irishman, working on railroads and in ditches, and living on potatoes. But the English greed which brought Paddy to this condition, has now reduced millions of our own high-spirited race to even lower conditions. They cannot get work on railroads, or ditches, or anything else, but are living on the thin soup of public charity ; while our cities are preparing, under the Pingree plan, to bring the free men of this country to the same sustenance of potatoes, as a steady diet, for which we used to despise poor landlord-impoverished Paddy. The Irishman, trained for generations in the school of English oppression and starvation, his stomach ensmalled by poverty, is better able to stand the persimmon diet of the present day than the child of the Declaration of Independence, who comes to it for the first time.”

“ Persimmon diet ! ” said Mr. Hutchinson, “ what do you mean by that ? ”

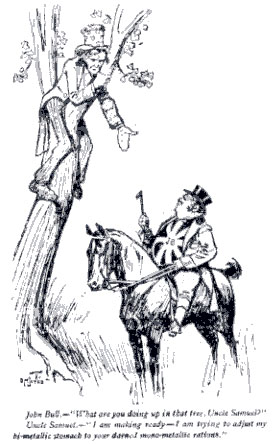

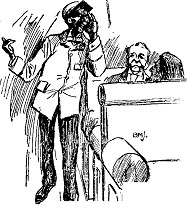

“ Have you not heard the old story ? ” replied Mr. Sanders. “ A regiment of confederate soldiers, during the civil war, were marching through a region of country that had been swept bare by the contending armies. They were half starved. The colonel rode up to a persimmon tree, and found one of his command up in the tree, eating the unripe fruit.

“ Have you not heard the old story ? ” replied Mr. Sanders. “ A regiment of confederate soldiers, during the civil war, were marching through a region of country that had been swept bare by the contending armies. They were half starved. The colonel rode up to a persimmon tree, and found one of his command up in the tree, eating the unripe fruit.

“ ‘ Bill,’ said he ‘ what are you doing there ? Those persimmons are not fit to eat.’

“ ‘ I know it, colonel,’ responded Bill, ‘ but I am trying to pucker up my stomach to the size of my rations., ”

“ Very good,” said Mr. Hutchinson, “ but really, in my friend, what has the volume of currency got to do with the prosperity of the people ? If a man can buy as much with fifty cents as he could with a dollar, what difference does it make to him ? ”

“ In other words, ” replied the farmer, “ if the confederate soldier could have sufficiently contracted his stomach by the aid of the persimmons, he could have lived as well on a half ration as as a whole one, and been equally vigorous and hearty. Is that what you mean ? ”

“ No ; that is an illustration, not an argument.”

“ An illustration,” replied the other, “ is oftentimes the highest argument. The parables of Christ made millions of converts whom his logic would never have reached. Our clearest thoughts are those that take the form of living figures. God thinks in facts and man in pictures. Weakness diffuses itself into theories ; strength boils the theories down into an incident.

“ Now,” he continued, “ let us test your proposition. You intimate it can do no harm to reduce the volume of the world’s currency one-half—that mankind will adjust itself to it. If this be so, then the same argument will hold true if we cut it down to one-fourth. Why not ? Where does the contraction cease to be reasonable and become unreasonable ? And if you can cut it down to one-fourth, why not to one-tenth ? Is there any limit to the adjustability of humanity to its environment ? If so, what is it ? Now, if this be true, why not abolish all forms of money, and fall back on primeval barter ? Man once existed without currency. Why can he not do so again ? ”

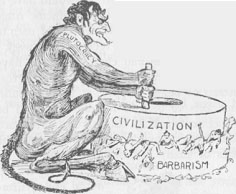

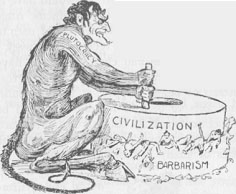

“ That would never do,” replied Mr. Hutchinson. “ That would end all borrowing and lending, all bonds and mortgages, all drafts, bills of exchange and promissory notes. It is absurd to talk of going back to barter. The banks would all have to close. They could not take wheat and potatoes on deposit. The lady who went shopping would have to fill her carriage with chickens, turkeys, quarters of beef, legs of mutton, turnips and cabbages. If a man took a street car, he would have to have a bag on his back, and when the conductor came around he would haul out two or three ears of corn to pay his fare. When the workman received his week’s wages in meat and vegetables and cloth, he would have to spend another week to trade them off. All the great staple crops, instead of being shipped, as now, in bulk, to the central markets to be sold for money, would be broken up into fragments and fly backwards and forward in carts and cars like a weaver’s shuttle, to answer the infinite necessities of many millions of people. Why, such a system would end civilization and send us all back to barbarism. Every citizen would have to have a cart for a pocket book. No, no ; that would never do. The proposition is absurd.”

“ That would never do,” replied Mr. Hutchinson. “ That would end all borrowing and lending, all bonds and mortgages, all drafts, bills of exchange and promissory notes. It is absurd to talk of going back to barter. The banks would all have to close. They could not take wheat and potatoes on deposit. The lady who went shopping would have to fill her carriage with chickens, turkeys, quarters of beef, legs of mutton, turnips and cabbages. If a man took a street car, he would have to have a bag on his back, and when the conductor came around he would haul out two or three ears of corn to pay his fare. When the workman received his week’s wages in meat and vegetables and cloth, he would have to spend another week to trade them off. All the great staple crops, instead of being shipped, as now, in bulk, to the central markets to be sold for money, would be broken up into fragments and fly backwards and forward in carts and cars like a weaver’s shuttle, to answer the infinite necessities of many millions of people. Why, such a system would end civilization and send us all back to barbarism. Every citizen would have to have a cart for a pocket book. No, no ; that would never do. The proposition is absurd.”

“ I am glad that you perceive that,” responded Mr. Sanders, “ for the point I desire to make is, that every reduction of the money of a country below an adequate per capita for the needs of the people, is an approximation toward the condition of no money at all. It is worse ; for humanity, if there was no currency in existence, nor pretence of any, would speedily adjust itself to its environment ; and would have no more need for money than the savage of Dahomey has. But you possess a state of development requiring an adequate supply of currency, and, at the same time, there are limitations placed upon it dragging down the people toward savagery, the human race is caught between the upper and nether millstones of civilization and barbarism, and ground into agony and wretchedness.”

“ I am glad that you perceive that,” responded Mr. Sanders, “ for the point I desire to make is, that every reduction of the money of a country below an adequate per capita for the needs of the people, is an approximation toward the condition of no money at all. It is worse ; for humanity, if there was no currency in existence, nor pretence of any, would speedily adjust itself to its environment ; and would have no more need for money than the savage of Dahomey has. But you possess a state of development requiring an adequate supply of currency, and, at the same time, there are limitations placed upon it dragging down the people toward savagery, the human race is caught between the upper and nether millstones of civilization and barbarism, and ground into agony and wretchedness.”

“ But what would you call an adequate supply of currency ? ” inquired the banker.

“ That is a difficult question to answer, ” replied the farmer. “ It must depend upon the condition of the people. If they are unprogressive, lethargic, and peasant-like it would require much less currency than that needed for a highly intellectual and intensely active people, turning out, with the aid of great inventions, an immense quantity of productions of all kinds. In December, 1865, Secretary of the Treasury McCulloch reported to Congress that ‘ the people are now comparatively free from debt.’ The workman owned his home and the farmer his farm, unencumbered by mortgages. There was work for every one. There were no tramps in the land.”

“ What caused that condition ? ” asked the banker.

“ Simply the fact that we had over sixty dollars per capita, of money, in circulation.”

“ That is impossible,” replied Mr. Hutchinson. “ We had not half that amount. We have nearly as much money in circulation now as we had then.”

“ What makes you think so ? ”

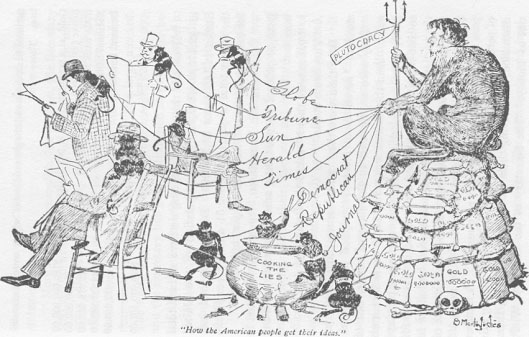

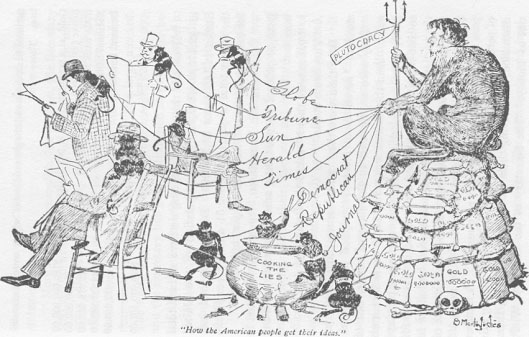

“ Why, that is the universal testimony of our daily press.”

THE PER CAPITA OF CURRENCY IN 1865.

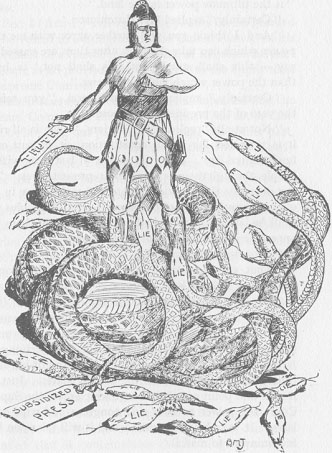

“ A consensus of opinion,” replied Mr. Sanders, “ on the part of the daily press of the United States, clearly establishes the opposite proposition ; and the more earnest and emphatic they are the greater the misrepresentation. There are not more than half a dozen papers that are an exception to this rule.”

“ That,” said the banker, “ is the view espoused by the anarchists. They call it the hireling press.”

“ I have nothing to do with the anarchists,” said the other, “ but a man may clearly perceive the cause of an evil and yet advocate an unwise remedy. I rest my assertion upon the following facts.

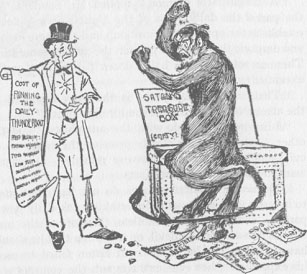

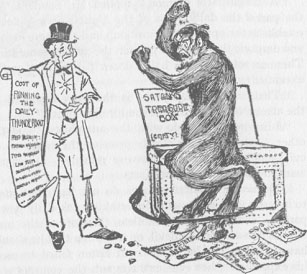

“ The men of moderate means do not have vast sums to invest in such precarious undertakings as daily newspapers. You remember, doubtless, the story of the man who sold his soul to the devil, on condition that he should have all the money he wanted. If Satan failed to meet his expenditures, however extravagant, the contract was to be at an end. After some years of riotous and prodigal profusion, the devil paying the bills promptly, our adventurer, seeing the end drawing near, determined to try to ‘bust’ Beelzebub. He began by gambling and losing wholesale. The devil never winced. Then he took to speculating in western real estate, still the money was advanced promptly. Then he built and operated a theatre ; the devil grumbled but paid up. Then he established a daily paper. At the end of six months his Satanic majesty told him he could go to—heaven ! That his darned old soul wasn’t worth what it was costing him,

“ The men of moderate means do not have vast sums to invest in such precarious undertakings as daily newspapers. You remember, doubtless, the story of the man who sold his soul to the devil, on condition that he should have all the money he wanted. If Satan failed to meet his expenditures, however extravagant, the contract was to be at an end. After some years of riotous and prodigal profusion, the devil paying the bills promptly, our adventurer, seeing the end drawing near, determined to try to ‘bust’ Beelzebub. He began by gambling and losing wholesale. The devil never winced. Then he took to speculating in western real estate, still the money was advanced promptly. Then he built and operated a theatre ; the devil grumbled but paid up. Then he established a daily paper. At the end of six months his Satanic majesty told him he could go to—heaven ! That his darned old soul wasn’t worth what it was costing him,

“ ‘ And Lucifer fled to his home again,

On the wings of a blasting hurricane ;

And left old Armonel to die

And sleep in the odor of sanctity.’

“ A man by honest industry can make a comfortable living and a moderate competency for old age ; that is all. If he desires a million he must make tens of thousands or hundreds of thousands of other men work for him, and take all the fruits of their toil above a mere living. Hence when it comes to establishing a daily newspaper, at a cost of a hundred thousand, or five hundred thousand dollars, the founders must be rich men. And if they go into such an enterprise it is to increase their wealth. And to do this the conditions which gave them their opportunities must be maintained ; and hence the paper must oppose all reform measures that would protect the many from the exactions of the few. And the friends of one kind of oppression are compelled, necessarily, to unite with those of all other forms of oppression ; and hence we have a gigantic power, undreamed of by our ancestors, which holds possession of all access to the brains and beliefs of the multitude, and is misleading them to their ruin. It is a diabolical contrivance and one of the greatest of the dangers which now threaten civilization. To get at the truth the people have to ‘read between the lines,’ or depend on books, pamphlets and the weekly newspapers ; and even a great part of these latter are but a weak echo of the dailies,—the editors bought to betray the people with some such trivial bribe as a free railroad ticket. Hence the outburst of pamphlets, which characterized the era of Queen Ann, is being repeated in this our present age. It is the effort of the chained and imprisoned intellect of man to obtain a hearing, despite the plutocratic power which has taken possession of all the avenues of public enlightenment.

“ This is all very pretty,” said Mr. Hutchinson, “ but it does not answer my assertion, that the people of the United States have as large a circulating medium to-day as they had in 1865.”

“ Well, I shall try to answer it,” replied Mr. Sanders.

“ Let us take up first the question as to how much circulation we had in 1865.

“ The Treasurer of the United States,” here he consulted a little book which he drew from his pocket, “ Mr. F.E. Spinner, he of the complicated signature, on page 244 of the finance report, 1869, says :

OUTSTANDING CIRCULATION.

“ Recapitulation of all kinds of government papers that were issued as money, or that were, in any way, used as a circulating medium :

“ Seven and three-tenths notes ; temporary loan certificates ; certificates of indebtedness ; six per cent. compound interest notes ; gold certificates ; three per cent. certificates ; old two year six per cent. notes ; one year five per cent notes ; two year five per cent. notes ; two year five per cent. coupon notes ; demand notes ; legal tender notes, and fractional currency.”

“ On pages 27 and 28 Messages and Documents, 1867-8, a public-debt statement shows that the following amounts of indebtedness, which the Treasurer of the United States declared were used as money, were in existence :

Certificates of indebtedness.................85,093,000.00

Five per cent. legal tender notes...........33,954,230.00

Compound interest legal tender notes..217,024,160.00

Seven-thirty notes..............................830,000,000.00

United States notes............................433,160,569.00

Fractional currency..............................26,344,742.51

Total.............................................$1,625,576,701.51

“ These were the obligations of the government, issued by the government, and used as money. Of the whole amount $634,138,959.00 were made by law legal tender. But in addition to these we must count in the gold and silver, the state bank notes, the national bank notes and the demand notes which were in circulation. These were :

Gold, at a premium, used to pay duties on imports ..$189,000,000.00

Silver (estimated)......................................................9,500,000.00

State bank notes....................................................142,919,638.00

National bank notes...............................................146,137,860.00

Demand notes.............................................................472,603.00

Total...................................................................$488,030,101.00

“ If we add this to the foregoing we have a grand total of $2,113,606,802.51. The population of the United States, in 1865, was 34,748,000. Divide this total into the money total of $2,113,606,802.51 and it gives $67.26 for each inhabitant. That was our per capita then.”

“ But,” said Mr. Hutchinson, “ you have counted in $830,000,000 of ‘seven-thirty notes’ as money. They were not.”

“ What were they ? ” asked the farmer. “ They were bonds.”

“ Why then were they called ‘seven-thirty notes’ instead of ‘seven-thirty bonds ’ ? ” replied Mr. Sanders.

“ They were not printed in the form of bonds, but of notes. And the interest was made $7.30 cents a year on $100 ; or twice 365 ; which is equal to two cents per day ; so that when the notes passed from hand it was easy for the parties to count up the accrued interest and allow in their dealings for it. This was the reason that rate of $7.30 was agreed upon. And that these 7.30 notes did pass from hand to hand there is no question. A number of persons have testified, in the newspapers, during this discussion, to receiving them as money and paying then out as money. The Secretary of the Treasury, W.P. Fessenden, on page 206 of his report, made the following statement :

“ ‘ More fully to accomplish his purpose, the Secretary resolved to avail himself of a wish expressed by many army officers and soldiers, through the paymasters, and offered to such as desired to receive their pay seven-thirty notes of small denominations. He was gratified to find that these notes were readily taken to a large amount. The whole amount thus disposed of exceeded $20,000,000 ; and the Secretary has great satisfaction in stating his belief that the disposal thus made was not only a relief to the treasury, but a benefit to the recipients as affording them an easy mode of transmitting funds to their families.’

“ This emphatically settles the question as to whether or not they were used as money. They paid off our armies in the midst of the great struggle for the unity of our territory. But their use was not confined to our officers and soldiers ; they were taken by the creditors of the government and readily passed from hand to hand, carrying their accumulating interest with them. It simply shows how desperate are the straits of the monometallists, and how unscrupulous are their methods when they would attempt to deny a fact that is within the knowledge and memory of hundreds of thousands of those yet living. A cause must be bad indeed that has to be defended by such flagrant falsehoods.”

“ But,” said the banker, “ the supply of currency was too great in 1865. It had to be reduced.”

CONTRACTION OF THE CURRENCY.

“ Not necessarily,” said the other. “ No one complained of too much money. The merchants and business men were more prosperous than they had ever been before in any age or country. The very capitalists were flourishing, for there were enterprises inviting investment on every hand, and every investment was prosperous. There were in 1865 but 530 failures in the United States ; in 1878, five years after the demonetization of silver, the number of failures had increased to 13,000 ! ”

“ But, surely,” said Mr. Hutchinson, “ the contraction of the currency was not the cause of this tremendous change ? It was due to the reaction from an era of overspeculation ; it was the sickness that follows the debauch.”

“ That is the usual comparison,” replied the other. “ You gentlemen seem to think that prosperity and happiness are a species of drunkenness, and that man’s normal condition is wretchedness and misery. And you so argue because in all the past ages the afflicted human family, darkened by ignorance, terrified by superstition, robbed by power, the prey of kings and queens, dukes and barons, tricksters and usurers, overrun by armies or engaged in almost perpetual war, merely survived on the planet, and thought it was happiness to be permitted to barely live. Hence they are ready to believe that an outburst of prosperity, such as followed our civil war, due to that $67 per capita, was a drunken debauch, a lunatical dream, and that the sooner it was ended, and they got back to their ancestral wretchedness, the better for them. But why should a period of universal prosperity and advancement be unnatural or, unreasonable, when the highest, most energetic, industrious and civilized people of the earth were spreading over the larger part of a continent, creating states, counties, cities, highways, and, armed with the marvelous powers of steam and electricity, releasing the stored-up, million-year-old resources of the fields and forests and mines ? To stop such a people in mid-career is the greatest crime ever committed on the globe. And it is adding the gravest insult to the profoundest villainy for a lot of money-lenders to tell the inhabitants of the conquered nation that their natural and proper condition is a state of helpless poverty and suffering. It is an army of Gullivers, giants, tied down by a score or two of little, cunning Lilliputians, in the midst of their wrecked resources ; not only overthrown, but lied to and deceived, which is the saddest and most disgraceful part of it.”

“ Very well said, from your standpoint,” interjected Mr. Hutchinson, “ but I do not see that you prove that a decrease of the currency produces the ruin of the people. Even in these hard times the banks are overflowing with money. There is more currency than the people can use.”

“ Very true,” said the other, “ but there is more blood in the head of the man stricken with apoplexy than he can make any use of. He dies from the unnatural engorgement. This country is in a state of apoplexy. The money has all gone to the banks. The extremities of the nation are cold and pulseless. The doctor who would say that the apoplectic patient was in an extraordinarily healthy condition because he had more blood in his head than any other man in three counties would be called a fool, and a fit subject for the insane asylum. Money is the life-blood of trade and social intercourse. It should flow with equal force to all parts of the body politic. Then the eyes are bright, the cheeks are red, the digestion is good, the footsteps quick and springy, and the whole man fulfilling the functions God gave him to perform. But when the money is all in the banks the country lies upon its back, powerless, helpless, while its stertorous breathing shows that death is near at hand.”

“ That is all theorizing,” said the banker, “ have you any proofs that your theory is correct ; that the prosperity of a people holds any relation to the amount of the circulating medium ? ”

“ The proof,” said the other, “ is the present condition of the United States as compared with the condition in 1865, just thirty years ago. But if you need further proof I can refer you to all the great thinkers of the world who have ever written upon the subject. The famous Scotch historian, David Hume, a man whose opinions are received to-day with universal respect, said :

“ ‘ Falling prices, misery and destitution are inseparable companions. The disasters of the Dark Ages were caused by decreasing money and falling prices. With the increase of money, labor and industry gain new life.’

“ The United States Monetary Commission, created August 15, 1876, made a report March 2, 1877, in which they said :

“ ‘ That the disasters of the Dark Ages were caused by decreasing money and falling prices, and that the recovery therefrom and the comparative prosperity which followed the discovery of America were due to an increasing supply of the precious metals and rising prices, will not seem surprising or unreasonable when the noble functions of money are considered. Money is the great instrument of association, the very fiber of social organism, the vitalizing force of industry, the protoplasm of civilization and as essential to its existence as oxygen is to animal life. Without money civilization could not have had a beginning, and with a diminishing supply it must languish, and unless relieved finally perish.’

“ The historian Allison states that when Christ was born there was $1,600,000,000 of gold and silver in the

Roman Empire, derived largely from the mines of Spain. But these mines became exhausted. The supply diminished ; the usurer plied his arts and the capitalist grasped the real estate ; all wealth was concentrated in a few hands, just as it is becoming to-day ; and the multitude were reduced to the lowest limit of degradation and wretchedness. They had no longer the courage or the public spirit of their forefathers, to defend their homes. And when a great white race, which had been nurtured in the storms and snows and ice of the remote north, a barbarous but noble people, schooled by suffering into heroism, a race of warriors and freemen, moved southward, toward the sun, and fell upon the imbecile aristocrats and degraded commonwealth of Rome, the mighty empire, once mistress of the known world, tumbled into a heap of ashes and was no more.

“ But as culture increased among the conquerors and the distinctions of society arose, the rich desired the luxuries of the orient ; and, as they had nothing except the precious metals which the Hindoos wanted, in exchange for their silks and satins, and spices and jewels, the gold and silver had to go, by the slow moving caravans, from Europe to Asia never to return. We are told that a gold coin loses one-thirteen-hundredth part of its weight every year. Hence in thirteen hundred years it would all be dissipated. From these conjoined causes it came to pass that by the ninth century (as Allison tells us) the supply of gold and silver, of the countries embraced in the former Roman empire, had decreased from $1,600,000,000 to $150,000,000, or less than one dollar in ten ! And as the coins became scarcer their exchangeable value necessarily increased, until a penny would buy a laborer’s wages for a day, and two pence would buy a sheep or a bushel of wheat.

“ We had what they call the Dark Ages. One writer observes : ‘ For a thousand years the mind of man made

not a single step in advance.’ A pall of desolation settled down on the human family. The very intellect of the race became torpid. But for the religious houses the arts of reading and writing would have disappeared, the alphabet have been lost, and civilization itself have perished in a black and sunless sea of barbarism. There were no wits, no poets, no historians, no orators for hundreds of years. The human race was practically dead.”

“ But,” said Mr. Hutchinson, “ did not the art of printing lift up the human family ? ”

“ The art of printing,” replied Mr. Sanders, “ was a noble invention, (or importation), and in these latter ages has worked tremendous results, but of what use was a process to make books to a man whose wages were a penny a day ? No. The ‘ renaissance,’—the resurrection of the human mind—was due to the increased supply of money in Europe, and the consequent increased activity in commerce, and the increased wealth. It

“ ‘ Put a spirit of life in everything,

Till jocund Nature laughed and leaped with it.’

“ The time had come when He who made man perceived that he was traveling towards an abyss ; and so He put it into the mind of an Italian adventurer to sail west to find India, and make a fortune out of pepper. His chief difficulty was that, in consequence of the rotundity of the globe, he believed he was going down hill as he went westward ; that was simple enough ; but how would he ever climb that watery hill to get back to Spain ? There was the rub ! But God makes use of blind instruments to do his greatest work ; and so this geographer, who believed that the East Indies lay where the West Indies are, and that the globe was shrunken by the whole width of the Pacific ocean, and who, in Cuba, sent an embassy to wait on the Grand Kahn, became the means by which the American continents were opened to overflowing Europe, and the gold and silver of Central America, Mexico and Peru were torn from the walls of the temples and converted into coin to lift up the white race to the splendid development it has since attained.

“ This it was that made the printing press available ; this breathed immense and potent life into the alphabet ; this made art triumphant, for there was something with which to buy its productions ; this warmed the genius of humanity into activity until Bacon, Cervantes, Montaigne and a thousand others came to adorn the pages of history. The increased supply of money, thus obtained, was supplemented by the creation of bank credit. This, like nearly all the great inventions or discoveries of value to mankind, was stumbled upon. In 1171 the city of Venice seized upon the wealth of its most opulent citizens by a forced loan ; it kept the money and gave the owners credit upon its books ; and these credits could never be withdrawn, but were transferable at the pleasure of the owners upon the books. They became of more value than coins of like amounts, and rose to a premium, because the coins were worn and chipped and of uncertain values. The system endured, with universal approval, for 626 years. It practically doubled the volume of the money which entered it, for the credit was the shadow of the coin. In the seventeenth century similar banking systems spread over Holland, Spain, France, England and Italy, having the effect to still farther increase the apparent volume of money and swell the growing flood of civilization, until it has reached its present enormous proportions.

URBAN AND RURAL INTELLIGENCE.

“ You seem, sir,” said Mr. Hutchinson, “ to have studied the financial question very thoroughly.”

“ I fear there is a covert sneer in what you say,” replied Mr. Sanders, “ for the business men of the cities usually feel that to be an agriculturist is to be a kind of serf and ignoramus. But this is an unjust conclusion. To handle money is not necessarily to know anything about the great laws of finance. The merchant’s whole art is to buy at wholesale and sell at retail ; to know his customers and to be keen and quick in looking after his collections. What is there in this that would give him any right to speak on great economic questions ? The tanner or the shoemaker, because they deal in hides, might just as well pretend to teach ex-cathedra as to the raising of cattle or the treatment of their diseases. The business man of the cities is absorbed in an infinite number of petty details of trade ; and if he has any time left, the theater, the concert hall, the club room, or the lecture hall call him away. On the contrary, the farmer is denied all these temptations to fritter away his time, and is forced to think and study. The city man reads the newspapers by glimpses at the headlines, snatched on the street cars ; the farmer devours the whole publication, down even to the editorials. Hence it is a curious fact that you can take hap-hazard a dozen intelligent country

residents and a like number of the inhabitants of the cities, and let them discuss the financial issues of the day, and it will be seen that the former are better informed as to the monetary history of our country than the latter. Thus it comes that the agricultural societies two or three years ago were discussing the questions which have only just now reached the horizon of the urban population.

“ The banker is an accumulator ; he has the squirrel’s instinct to gather nuts ; his mind is usually devoid of any thought but a vehement desire to obtain riches. He knows the financial standing of every man who deals with him, and he rates each one, not by his knowledge of his virtue or his character, but by his bank account. His maxim is, ‘ D——n your reputation ; take care of your credit.’ A Dunn or Bradstreet report is his Bible—his encyclopaedia—and he studies it with rapt devotion. But you might just as well expect the nut-gathering squirrel to give (if he could speak) some valuable suggestions to Linneus or Darwin, as to the relations of the Rodentia to the rest of the animal kingdom, as to suppose that mere money-lenders would know anything about statesmanship or the government of nations. The squirrel could tell the philosophers how best to climb a tree with a nut in one’s mouth, or how to recognize a worm-hole ; that is all. The money-lender is profoundly keen in finding out how much of a mortgage is on a neighbor’s house, or how much the fellow around the corner, who owns a junk shop, is in debt. But what has that got to do with the great philanthropic purposes which lie at the base of civilization ? And how can a man whose life has been spent in concentrating the wealth of the many into the pockets of the few, so conduct the affairs of government that the inordinate greed of the great plunderers of the world shall be restrained and the many be lifted up to happiness ? ”

“ Do you mean to say that an inhabitant of a city cannot form correct conclusions on public affairs ? ” asked Mr. Hutchinson.

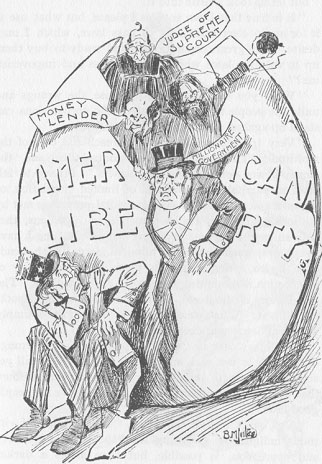

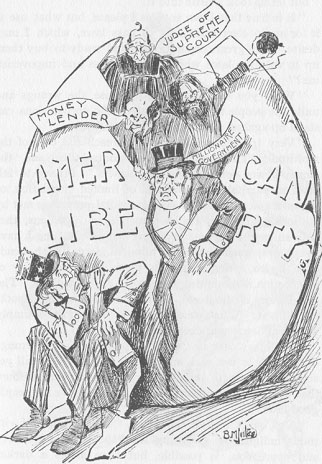

“ Not at all,” replied the other, “ some of the most benevolent hearts and clearest brains in the world have come from cities. What I am trying to make plain is, that money-lending is not a proper preparation for statesmanship ; and that mere success in nut-gathering does not imply capacity for governing. Now-a-days our craven-spirited people are down on their knees before the millionaires, and asking them to rule the land ; and they are nothing loathe to do so. Indeed, as their criterion is the bank account, they naturally push themselves forward and are striving to change our government from a republic of equality to an oligarchy of wealth, and they are rapidly accomplishing their purpose. Only the shell of liberty remains to-day.”

THE AGGRESSIVENESS OF THE COURTS.

“ Really, my dear sir,” said Mr. Hutchinson, “ I have listened to you with a great deal of interest, because you seem to have positive convictions so different from my own conclusions, but when you say that only the shell of liberty remains in tire republic of the United States, you say that which, (pardon me) seems to me absurd. Where can you find more liberty than there is in this country ? You can speak and print whatever you please ; you call denounce the government as you are now doing, with impunity ; and you can vote as you please, for whomsoever and whatsoever you please. Where can you find greater liberty than that ? ”

“ Really, my dear sir,” said Mr. Hutchinson, “ I have listened to you with a great deal of interest, because you seem to have positive convictions so different from my own conclusions, but when you say that only the shell of liberty remains in tire republic of the United States, you say that which, (pardon me) seems to me absurd. Where can you find more liberty than there is in this country ? You can speak and print whatever you please ; you call denounce the government as you are now doing, with impunity ; and you can vote as you please, for whomsoever and whatsoever you please. Where can you find greater liberty than that ? ”

“ All that appears to be true,” replied Mr. Sanders, “ but let us look a little into it.

“ It is true that I can vote as I please, but what use is it for me to elect legislators to pass laws, which I may desire, when great corporations stand ready to buy them up to vote for laws which will oppress and impoverish me ? ”

“ Well, you can agitate and expose the wrongs and unite the people to reform abuses. No corporations can stand up against a united public opinion.”

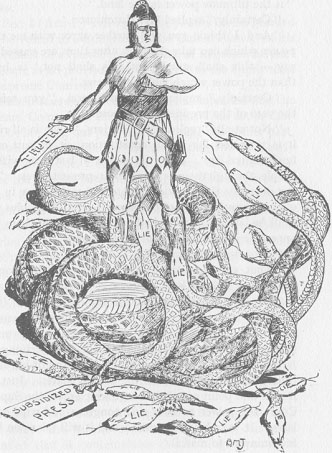

“ Very true ; but how am I to reach the ears of the multitude ? The great newspapers control them, and ‘ the money-power controls the newspapers.’ I have to fall back on pamphlets or journals of limited circulation, or my own voice. And every argument I present is met by millions of printed lies so plausible, so ingenious, that only an expert can answer them ; and by the time I have swept away one falsehood, a hundred more, like the heads of a hydra, spring up in its place. The ingenuity of falsification is something unparalled and appalling. The past history of the world, as I have said, furnishes nothing like it. What we call popular ignorance is simply universal newspaper deception.”

“ Well, my dear sir,” said the banker, “ if the wrongs of the people are real and not imaginary they will yet arise in their wrath and elect legislators and congressmen that will beat down the corruptionists and give the people good laws.”

“ Well, my dear sir,” said the banker, “ if the wrongs of the people are real and not imaginary they will yet arise in their wrath and elect legislators and congressmen that will beat down the corruptionists and give the people good laws.”

“ Yes, sir,” replied the other, “ such a spasm of virtuous indignation, springing from the bosom of poverty and oppression, is possible, but then arises a darker danger.”

“ What is that ? ”

“ You will agree with me that whatever makes the laws for the government of the people,” said Mr. Sanders, “ is the ultimate power in the land.”

“ Certainly,” replied Mr. Hutchinson.

“ And I think you will further agree with me that a power which can take the laws after they are passed, and say :—‘ this shall stand—but this shall not,’ is higher than the power which makes the laws.”

“ Certainly,” replied Mr. Hutchinson, “ you refer to the veto of the president, I suppose.”

“ Not at all,” replied Mr. Sanders, “ that is all right ; it is provided for in the constitution ; it is part of the fundamental law. And the power at last rests with the people, through their senators and representatives. They can over-ride the president’s veto and make a law in spite of the executive. But the power I refer to decides what shall be law and what shall not be law, and there is no appeal, under heaven, from its decision.”

“ I don’t understand you.”

“ That power is the United States Supreme Court in the nation, and the local supreme courts in the states.”

“ Oh, that’s all right,” replied Mr. Hutchinson, “ they are given that power in the national and state constitutions. They have the right to declare any law unconstitutional. I did not know what you were driving at.”

“ Well, ” said the other, taking a book out of his valise, “ here is the constitution of the United States. Just look it over and point out the passage which gives the Supreme Court the power to over-ride congress and wipe out its laws. It is a brief document and it will take you but a few minutes to read it.”

After a pause Mr. Hutchinson replied :

“ I am very much surprised ; there is nothing here of the kind.”

“ Precisely,” said the other. “ On the contrary you will find that the opening words of the constitution are as follows :

“ ‘ Sec. I (Art. I.) All legislative powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States, which shall consist of a Senate and a House of Representatives.’

“ There is no proviso here—‘ subject to the approval of the Supreme Court of the United States.’

“ If the framers of the constitution had intended that the Supreme Court had the right to amend an act of Congress, by striking out part and approving of another part, all of which are legislative functions, they would clearly have said so. Sec. 2 of Article III prescribes the limitation of the judicial powers, naming the different parties to actions, as controversies between two or more states, between a state and the citizens of another state, between citizens of different states, etc.; but it no where provides for bringing the United States or Congress before the court to test the validity of its laws. In fact so jealous were the people of the encroachments of an irresponsible judiciary that the same generation which adopted the constitution adopted an amendment to it, the XI, March 5, 1794, providing :

“ ‘ The judicial power of the United States shall not be construed to extend to any suit at law or equity, commenced or prosecuted against one of the United States, by citizens of another State, or by citizens or subjects of any foreign State.’

“ If the constitution thus inhibits the dragging of a State into court, in the instances referred to, can it be pretended that it contemplates establishing a power in the Supreme Court to pass a wet sponge over all the enactments of Congress, or over any one act ; and that it

nevertheless nowhere clearly asserts that right in the letter of the constitution. The fact is that Thomas Jefferson, third president of the United States, author of the Declaration of Independence, and the greatest statesman the soil of America has produced, declared, until the hour of his death, that the Supreme Court had no such power to over-ride Congress ; and it was indeed twelve years before the court dared to assume such a power ; and then it was done by Chief Justice Marshall, as a part of the Hamiltonian programme to turn the republic into an aristocracy, looking to an eventual monarchy.”

“ But, ” said Mr. Hutchinson, “ may not the Congress violate the direct letter of the constitution, and is it not necessary that a restraining power should exist somewhere ? ”

“ True it is,” said the farmer, “ that ultimate and absolute power must, in the last resort, be lodged somewhere ; and such power implies the right to make mistakes ; but where can it be so safely lodged as in the Congress of the United States, which is merely the mouth-piece of the entire people ? Every two years the popular branch of Congress has to go back to the people, for endorsement or repudiation ; and, if they have made mistakes or transcended the limitations of the constitution, there the mistakes can be corrected and the offenders punished. But on the other hand the Supreme Court is composed of a few men holding their places for life, with no power of appeal to anything above them. In England, if a court does wrong, there remains the right to go into the House of Lords, to seek a revision of the erroneous judgment, but the House of Lords is part of the legislative department, and not the judicial.”

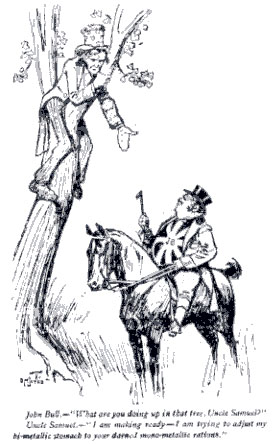

“ But,” said the banker, “ can not the Supreme Court of England set aside an act of Parliament as unconstitutional ? ”

“ Certainly not. Nothing of the kind was ever heard of or dreamed of. Englishmen would rise in revolution against any proposition to place the whole power of deciding what laws should govern them in the hands of a dozen lawyers selected by the crown. The queen herself, during her whole reign, has never dared to veto any act of Parliament demanded by the people. Her dynasty would not endure twenty-four hours if she did, and she knows it. The English people have not the craven spirit which has been indoctrinated into our own people by the plutocracy, through a servile daily press. Parliament is omnipotent. No written constitution exists to shackle its limits. There is no limit to the scope, height, depth or variety of its action. It is simply the will of the English people, not tied up with parchment thongs and bandages, but free as God made them. Charles I. lost his head for a less offense against human liberty than these judges of ours are perpetrating. He was simply defending certain ancient prerogatives of the Executive. He never pretended that he could take the statute books of England and tear out all laws that did not meet with his approval. They would have burned him alive at the stake if he had attempted it.”

“ Certainly not. Nothing of the kind was ever heard of or dreamed of. Englishmen would rise in revolution against any proposition to place the whole power of deciding what laws should govern them in the hands of a dozen lawyers selected by the crown. The queen herself, during her whole reign, has never dared to veto any act of Parliament demanded by the people. Her dynasty would not endure twenty-four hours if she did, and she knows it. The English people have not the craven spirit which has been indoctrinated into our own people by the plutocracy, through a servile daily press. Parliament is omnipotent. No written constitution exists to shackle its limits. There is no limit to the scope, height, depth or variety of its action. It is simply the will of the English people, not tied up with parchment thongs and bandages, but free as God made them. Charles I. lost his head for a less offense against human liberty than these judges of ours are perpetrating. He was simply defending certain ancient prerogatives of the Executive. He never pretended that he could take the statute books of England and tear out all laws that did not meet with his approval. They would have burned him alive at the stake if he had attempted it.”

“ Dinner ready in the dining car,” cried the porter.

“Let us get something to eat,” said Mr. Hutchinson, “ and while I am eating I will digest your novel views.”

“ No ; they will do their best. But the human family having once risen out of serfdom cannot be forced back into it. There will be struggles and conflicts, perhaps revolutions and wars ; sometimes the people will be prostrate upon their backs, chained hand and foot ; and again they will be up with flashing and unobscured eyes, striking right and left, like a thresher with his flail. The contest may terminate in a few years, or it may run through centuries ; but ‘ there is a power in nature which makes for goodness, and evil is not to be our god. The Everlasting Justice will not permit the millions to starve that the thousands may be overwhelmed with hog-like superfluity.”

“ No ; they will do their best. But the human family having once risen out of serfdom cannot be forced back into it. There will be struggles and conflicts, perhaps revolutions and wars ; sometimes the people will be prostrate upon their backs, chained hand and foot ; and again they will be up with flashing and unobscured eyes, striking right and left, like a thresher with his flail. The contest may terminate in a few years, or it may run through centuries ; but ‘ there is a power in nature which makes for goodness, and evil is not to be our god. The Everlasting Justice will not permit the millions to starve that the thousands may be overwhelmed with hog-like superfluity.” “ Have you not heard the old story ? ” replied Mr. Sanders. “ A regiment of confederate soldiers, during the civil war, were marching through a region of country that had been swept bare by the contending armies. They were half starved. The colonel rode up to a persimmon tree, and found one of his command up in the tree, eating the unripe fruit.

“ Have you not heard the old story ? ” replied Mr. Sanders. “ A regiment of confederate soldiers, during the civil war, were marching through a region of country that had been swept bare by the contending armies. They were half starved. The colonel rode up to a persimmon tree, and found one of his command up in the tree, eating the unripe fruit. “ That would never do,” replied Mr. Hutchinson. “ That would end all borrowing and lending, all bonds and mortgages, all drafts, bills of exchange and promissory notes. It is absurd to talk of going back to barter. The banks would all have to close. They could not take wheat and potatoes on deposit. The lady who went shopping would have to fill her carriage with chickens, turkeys, quarters of beef, legs of mutton, turnips and cabbages. If a man took a street car, he would have to have a bag on his back, and when the conductor came around he would haul out two or three ears of corn to pay his fare. When the workman received his week’s wages in meat and vegetables and cloth, he would have to spend another week to trade them off. All the great staple crops, instead of being shipped, as now, in bulk, to the central markets to be sold for money, would be broken up into fragments and fly backwards and forward in carts and cars like a weaver’s shuttle, to answer the infinite necessities of many millions of people. Why, such a system would end civilization and send us all back to barbarism. Every citizen would have to have a cart for a pocket book. No, no ; that would never do. The proposition is absurd.”

“ That would never do,” replied Mr. Hutchinson. “ That would end all borrowing and lending, all bonds and mortgages, all drafts, bills of exchange and promissory notes. It is absurd to talk of going back to barter. The banks would all have to close. They could not take wheat and potatoes on deposit. The lady who went shopping would have to fill her carriage with chickens, turkeys, quarters of beef, legs of mutton, turnips and cabbages. If a man took a street car, he would have to have a bag on his back, and when the conductor came around he would haul out two or three ears of corn to pay his fare. When the workman received his week’s wages in meat and vegetables and cloth, he would have to spend another week to trade them off. All the great staple crops, instead of being shipped, as now, in bulk, to the central markets to be sold for money, would be broken up into fragments and fly backwards and forward in carts and cars like a weaver’s shuttle, to answer the infinite necessities of many millions of people. Why, such a system would end civilization and send us all back to barbarism. Every citizen would have to have a cart for a pocket book. No, no ; that would never do. The proposition is absurd.” “ I am glad that you perceive that,” responded Mr. Sanders, “ for the point I desire to make is, that every reduction of the money of a country below an adequate per capita for the needs of the people, is an approximation toward the condition of no money at all. It is worse ; for humanity, if there was no currency in existence, nor pretence of any, would speedily adjust itself to its environment ; and would have no more need for money than the savage of Dahomey has. But you possess a state of development requiring an adequate supply of currency, and, at the same time, there are limitations placed upon it dragging down the people toward savagery, the human race is caught between the upper and nether millstones of civilization and barbarism, and ground into agony and wretchedness.”

“ I am glad that you perceive that,” responded Mr. Sanders, “ for the point I desire to make is, that every reduction of the money of a country below an adequate per capita for the needs of the people, is an approximation toward the condition of no money at all. It is worse ; for humanity, if there was no currency in existence, nor pretence of any, would speedily adjust itself to its environment ; and would have no more need for money than the savage of Dahomey has. But you possess a state of development requiring an adequate supply of currency, and, at the same time, there are limitations placed upon it dragging down the people toward savagery, the human race is caught between the upper and nether millstones of civilization and barbarism, and ground into agony and wretchedness.” “ The men of moderate means do not have vast sums to invest in such precarious undertakings as daily newspapers. You remember, doubtless, the story of the man who sold his soul to the devil, on condition that he should have all the money he wanted. If Satan failed to meet his expenditures, however extravagant, the contract was to be at an end. After some years of riotous and prodigal profusion, the devil paying the bills promptly, our adventurer, seeing the end drawing near, determined to try to ‘bust’ Beelzebub. He began by gambling and losing wholesale. The devil never winced. Then he took to speculating in western real estate, still the money was advanced promptly. Then he built and operated a theatre ; the devil grumbled but paid up. Then he established a daily paper. At the end of six months his Satanic majesty told him he could go to—heaven ! That his darned old soul wasn’t worth what it was costing him,

“ The men of moderate means do not have vast sums to invest in such precarious undertakings as daily newspapers. You remember, doubtless, the story of the man who sold his soul to the devil, on condition that he should have all the money he wanted. If Satan failed to meet his expenditures, however extravagant, the contract was to be at an end. After some years of riotous and prodigal profusion, the devil paying the bills promptly, our adventurer, seeing the end drawing near, determined to try to ‘bust’ Beelzebub. He began by gambling and losing wholesale. The devil never winced. Then he took to speculating in western real estate, still the money was advanced promptly. Then he built and operated a theatre ; the devil grumbled but paid up. Then he established a daily paper. At the end of six months his Satanic majesty told him he could go to—heaven ! That his darned old soul wasn’t worth what it was costing him,

“ Really, my dear sir,” said Mr. Hutchinson, “ I have listened to you with a great deal of interest, because you seem to have positive convictions so different from my own conclusions, but when you say that only the shell of liberty remains in tire republic of the United States, you say that which, (pardon me) seems to me absurd. Where can you find more liberty than there is in this country ? You can speak and print whatever you please ; you call denounce the government as you are now doing, with impunity ; and you can vote as you please, for whomsoever and whatsoever you please. Where can you find greater liberty than that ? ”

“ Really, my dear sir,” said Mr. Hutchinson, “ I have listened to you with a great deal of interest, because you seem to have positive convictions so different from my own conclusions, but when you say that only the shell of liberty remains in tire republic of the United States, you say that which, (pardon me) seems to me absurd. Where can you find more liberty than there is in this country ? You can speak and print whatever you please ; you call denounce the government as you are now doing, with impunity ; and you can vote as you please, for whomsoever and whatsoever you please. Where can you find greater liberty than that ? ” “ Well, my dear sir,” said the banker, “ if the wrongs of the people are real and not imaginary they will yet arise in their wrath and elect legislators and congressmen that will beat down the corruptionists and give the people good laws.”

“ Well, my dear sir,” said the banker, “ if the wrongs of the people are real and not imaginary they will yet arise in their wrath and elect legislators and congressmen that will beat down the corruptionists and give the people good laws.” “ Certainly not. Nothing of the kind was ever heard of or dreamed of. Englishmen would rise in revolution against any proposition to place the whole power of deciding what laws should govern them in the hands of a dozen lawyers selected by the crown. The queen herself, during her whole reign, has never dared to veto any act of Parliament demanded by the people. Her dynasty would not endure twenty-four hours if she did, and she knows it. The English people have not the craven spirit which has been indoctrinated into our own people by the plutocracy, through a servile daily press. Parliament is omnipotent. No written constitution exists to shackle its limits. There is no limit to the scope, height, depth or variety of its action. It is simply the will of the English people, not tied up with parchment thongs and bandages, but free as God made them. Charles I. lost his head for a less offense against human liberty than these judges of ours are perpetrating. He was simply defending certain ancient prerogatives of the Executive. He never pretended that he could take the statute books of England and tear out all laws that did not meet with his approval. They would have burned him alive at the stake if he had attempted it.”

“ Certainly not. Nothing of the kind was ever heard of or dreamed of. Englishmen would rise in revolution against any proposition to place the whole power of deciding what laws should govern them in the hands of a dozen lawyers selected by the crown. The queen herself, during her whole reign, has never dared to veto any act of Parliament demanded by the people. Her dynasty would not endure twenty-four hours if she did, and she knows it. The English people have not the craven spirit which has been indoctrinated into our own people by the plutocracy, through a servile daily press. Parliament is omnipotent. No written constitution exists to shackle its limits. There is no limit to the scope, height, depth or variety of its action. It is simply the will of the English people, not tied up with parchment thongs and bandages, but free as God made them. Charles I. lost his head for a less offense against human liberty than these judges of ours are perpetrating. He was simply defending certain ancient prerogatives of the Executive. He never pretended that he could take the statute books of England and tear out all laws that did not meet with his approval. They would have burned him alive at the stake if he had attempted it.”