Outlaw Associations

Dancin' and Dates at Shady Rest

by William R. Carr

|

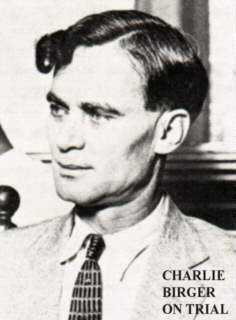

Charlie Birger — that Knight of Another Sort —

seems to be ever-popular in Southern Illinois. As a one-time soldier, cowboy,

and bronc-buster, and the romantic qualities of Robin Hood after he commenced

his outlaw career, Charlie had many of the requisites of an American folk hero.

He will certainly remain an integral part of the region's folklore. If not quite

"popular" with some, he at least continues to evoke considerable

interest, especially around Harrisburg where many saw him as hero rather than

hoodlum.

Gangsters and outlaws loom large and

significant in our rather colorful regional history. Though I suspect those

"good old days" seem colorful only in retrospect — with the

passing of sufficient time to render up a sense of security and safety in

our relatively tranquil present. I think it is probably natural, given the

passage of time, that some of us enjoy basking in a little reflected glory (or

reverse glory), from past family associations with the more colorful players of

times past. It seems that almost everybody in these parts has a Charlie Birger

tale or two to tell, and I think they should all be told.

Yours truly admits to a slight fascination with our historic

outlaw eras and their principle participants, and even an inexplicable tinge of

pride at having ancestors who were right in there with the worst of them. Of

course that tinge of pride would be less inexplicable, and perhaps even

understandable, had any of my ancestors been among the heroic champions of law

and order, rather than on the other side of the fence. Unfortunately, that isn't

the case, although I'll have to admit (or plead), that the overwhelming majority

of my ancestors have been upstanding citizens. The nearer those ancestors

approach myself, of course, the better they got. In fact, I know of one or two

fairly close relatives I can actually brag about openly and honestly. Honest.

In the present case, with a view toward maybe fleshing out

the saga of Charlie Birger somewhat, albeit with some rather obscure and

unimportant tidbits, I thought I'd troop out my little store of family tradition

in the interests of perversity, and for the benefit of posterity. Now that most

of the respectable (or more sensitive), members of the older generation have

passed on, I can do this without fear of embarrassing anybody — except,

perhaps, myself.

Our Birger associations come from both the paternal and

maternal sides of my family.

|

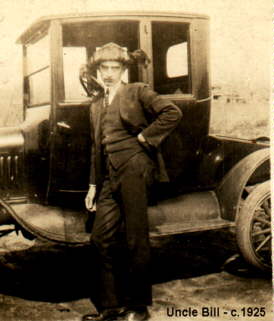

My great Uncle Bill

Gurley, after whom I take my first name, occasionally worked on

Charlie Birger's automobiles at his place of employment as a

mechanic on Harrisburg's west side. Though he, like just about

everybody else in Harrisburg, knew Charlie in passing, he

never claimed to be his friend. But he said Charlie provided them

with plenty of work, was jovial, and always conducted himself as a

gentlemen. He told of one time when Charlie came to the garage and told everybody they'd better clear out for awhile. Charlie said he expected a visit from some of the Shelton gang, and there might be some shooting. The employees cleared out for a little unscheduled coffee break. Whether or not the Sheltons showed up, and shots were fired, is uncertain. |

By far, our closest family associations with

notorious characters have been on my father's paternal side. My father is fond

of expressing the opinion that his father's branch of the family, while perfectly

respectable back east, "had mixed up," (in Mike Fink's vernacular),

"with horses and alligators during its pioneer march westward."

Our supposed outlaw associations range way back to the early

1800's and my five times great uncle — one of the area's earliest settlers.

This was Isaiah L. Potts, of

Potts' Tavern fame. Though I personally believe old uncle Isaiah is getting

somewhat of a bum rap in the "Legend

of Billy Potts," there's no denying that he was an associate of

"Satan's Ferryman" himself, James Ford. But those were rough, tough,

and lawless, times on the as yet untamed frontier.

In more recent times, some of this same clan found Charlie

Birger pleasant company. When Charlie first set up shop in our area, sometime

around 1913, it was in a little "store" at Ledford, just southwest of

Harrisburg. Less than a mile to the east of that establishment was the farm of

Joseph Potts, my great-grandfather. It seems my great-grandfather's family and

the Birgers became amicable neighbors and some lasting friendships ensued. My

grandmother, Sybil Gurley, had married my grandfather (Joseph, Jr.), only a few

years prior to Birger's arrival. This family friendship, and the associations it

engendered, became something of an embarrassment to the Gurley side of the

family. Later on, Sybil divorced Joseph Jr. and her second husband officially

adopted her children in 1918, changing their surname. This partially alleviated

some of the embarrassing social stigma the original name had caused.

|

At left: Joe Potts, Jr., my grandfather.

The photo at right, believed to be his younger sister, Ollie, was taken on the same day, though the identity is uncertain. |

|

Though details and verification are lacking, my father claims

that my grandfather ran an "establishment" for Charlie for a while

located somewhere on North Main Street in Harrisburg. My great aunt, Ollie

Potts, of course, became Charlie's long-time housekeeper and Girl Friday — and

some claim the relationship was much more than just that (both personally and

professionally).

According to Ruby Brown (one of Ollie's nieces), Ollie also conducted a romantic liaison with Connie

Ritter, which caused some serious friction between the Birger and Ritter. Ruby

also claimed (contrary to the reasons given in the books on the subject), that

when Shady Rest was burned, it was the result of jealous rage on Birger's part,

and a failed attempt on Ritter's life.

Aunt Ollie was noteworthy in her own right. Both attractive

and adventurous, she was once a circus motorcycle dare-devil who rode around,

and upside down, inside a large barrel cage, and (according to Ruby), did a little aerial

wing-walking on the side. My father says Ollie was known as Kitty La Dare during

her circus days. At one point in her life (and I learned it from an impeccable

non-family source), she is said to have gone by the handle of the "Queen of

Sheeba." Most likely, this was a title Birger's cohorts pinned on her.

Perhaps she seemed to enjoy an unduly exulted status in the gang. The same

source also told me that she and one of her later boyfriends made the sojourn up

to Menard penitentiary to visit Connie Ritter, who was then in residence.

Apparently the meeting didn't go particularly well, since Mr. Ritter wasn't pleased to share the visit with Ollie's new beau.

One of my father's most prominent memories of his

grandfather's farm was catching a glimpse of one of Charlie Birger's young

daughters skinny dipping in the farm pond. My dad, James

Robert Carr, was pretty small at the time (as was the young lady), but old

enough to be interested.

He was prevented from fully satisfying his boyish curiosity,

however. "A bunch of old ladies were standing around," he said,

"and kept me from getting a good look." He also remembers his

grandfather's fine watermelon patch, which probably provided Charlie with some

of the watermelons he took pride in selling at his store.

|

My aunt Flo remembered Charlie during his early years at the Ledford establishment, where he was a favorite with the local children. |

Flo was a pretty spunky young woman with a sense

of humor to match. She told me of one exploit some years later at the Red Bird

Inn, at Herod, during that settlement's more lively period. There was a certain

deputy sheriff who she said would come in strutting like a rooster. On the

subject occasion he came in acting like he owned the world, with an

"everybody better beware" continence. His obvious superiority complex,

and overly authoritative demeanor, made him a shoe-in for one of Flo's practical

jokes. As he stood next to her at the bar, surveying the clientele with a

jaundiced eye, she deftly lifted his pistol out of its holster and secreted it

in her purse.

Some of the customers saw what she'd done and began to giggle

and laugh, much to the officer's consternation and annoyance. When he discovered

that he was unarmed, his discomfiture was complete. He was not at all in a good

humor, perceiving himself the subject of such amusement.

Red faced, he looked at Flo, who could not contain her mirth.

He demanded the return of his side-arm, threatening to arrest Flo if she didn't

give it up. In turn, she refused to return his artillery unless he promised not

to arrest her. She suggested that he buy her a drink instead. He wasn't that

generous, but didn't arrest her when she finally relinquished his side-arm. He

left in an embarrassed huff — making a somewhat lackluster attempt to maintain

his cock-of-the-walk poise.

|

When the smooth, young, Connie Ritter breezed

into Harrisburg from points north, Flo was impressed by his sharp dress and

cosmopolitan flair. She was flattered when he asked her out on a date. She said

he was a wonderful gentleman and they'd had a grand time on their outing to

Shawneetown. But when the family found out who he was — that he was a Birger

henchman — the fledging relationship was brought to an abrupt end. Mr. Ritter

later conducted a romantic liaison with his boss's "housekeeper" —

Flo's aunt Ollie, who never shied from her associations with Charlie and his

gang.

|

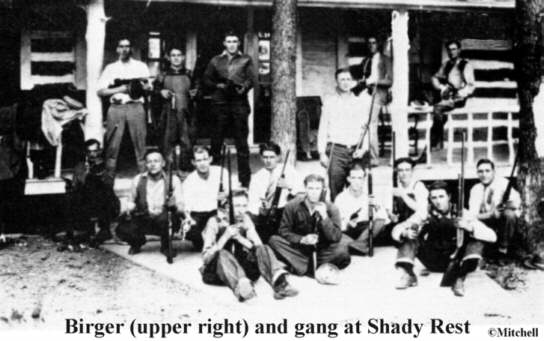

Charlie's establishment at Shady Rest, on

Route 13 half way between Harrisburg and Marion, was a popular stopping place

for many who traveled between those towns. As Birger's main roadhouse and

headquarters, it was more than just a road-side Bar-B-Q stand, of course. It was

a drinking establishment and a house of entertainment.

It was here that another of my relatives, Willard St. John,

often stopped for a little refreshment on his way home to Harrisburg from the

coal mine where he worked. Willard had been present, maybe a participant, at

another of Southern Illinois' more lamentable episodes — the Herrin Massacre.

He knew Charlie and considered him a friend. Gary DeNeal acknowledged Willard as

one of his many sources in his book A Knight of Another Sort.

Willard liked to tell of one occasion at Shady Rest when one

of Birger's men decided he'd like to see Willard dance. Willard found the

proposition sufficiently compelling, in the face of of a pulled revolver pointed

at his lower torso, to do a vigorous little gig for the ruffian's personal

entertainment. Willard said he put all he had into it, though he'd never

considered himself much of a dancer before that time. Before the dance was over

(and there was no indication that the audience was satisfied), Charlie came in

and quickly put a stop to it, roundly rebuking his fun-loving associate. But

Willard, after thanking Charlie, was advised that it might be better to leave,

and he left without finishing his beer.

There was another story Willard told, similar to the one my

Uncle Bill told above. Willard was at Shady Rest when Charlie and his men came

in and told his customers that they'd best get out for a while. The Sheltons

were supposed to be on their way. Once again, Willard didn't finish his beer,

and he said he heard shooting before he was half a mile down the road.

|

Shady Rest became a popular place for daring

young men to take their dates. Whether just to the Bar-B-Q stand, or a bold

foray into the main establishment, bold young men of the day considered Shady

Rest a cool place to take their lady friends.

Aunt Flo told me of one of her dates who took her to Shady

Rest to impress her with his boldness. The young man drove into the parking area

and the couple were still in their car when Charlie Birger drove up and emerged

from his vehicle. Recognizing Flo, Charlie approached the couple's car.

"Why, there's Charlie Birger!" Flo exclaimed to her

date. The young man, who had no idea that Flo and Charlie were old

acquaintances, was a little surprised at the familiar manner with which his date

greeted the famed gangster. The young man wondered why Charlie was headed right

in their direction as if he had some special interest in them. Charlie stopped

on the passenger side of the vehicle and looked across at the young driver.

Much to the young man's discomfiture, Charlie looked him

straight in the eye and demanded, "What are you doing with my girl?"

He made the inquiry with a false show of anger, followed,

after a calculated pause, with a friendly smile. While the smile eased the boy's

apprehension somewhat, Flo said his boldness and gaiety had visibly wilted. He

was at a loss for words. His waning apprehension changed to palpable alarm an

instant later, however, when he saw Charlie pull his pistol out of its holster

and waved it in his direction.

Still smiling, Charlie inverted his pistol and playfully

tapped Flo lightly on the head with the butt. Then Birger laughed and said,

"Now you can say you've been hit over the head by Charlie Birger's gun."

Charlie engaged the couple in a little small talk for a few

minutes. Most of the exchange was with Flo, as her friend seemed a little

withdrawn, and disinclined to say much. Then, bidding them a cheerful adieu,

Charlie left them to go on about his business.

Flo said that had been her first and last date with the

companion of the day. He never asked her out again.

|

|

My maternal grandfather, Albert Goodman, a long-time resident of Gaskin's City, was a well respected Harrisburg mine inspector for many years. Family tradition has it (to my grandmother's lasting chagrin), that he was one of Charlie's poker buddies at frequent friendly games. Aside from that, the extent of the relationship was that of grandpa drinking too much of Charlie's bootleg beer and liquor. |

Though my grandfather had a good job, he

was always broke and in debt, due to his poker playing, boozing, and other

escapades. This left little cash for the necessities of life, such as groceries

and heating coal. His daughters often found themselves having to go out on cold

mornings and collect "gob" (coal mine tailings used for gravel), from

the road to heat the house.

Since Charlie was known as a good Samaritan, my aunt Martha

remembers wishing he would drop them off a little coal, as he was known to do

from time to time at the households of the poor. Her wish never came true.

Albert always claimed that Charlie was a likable gentleman. That

claim didn't sit well with my grandmother (Ruth [Grace]

Goodman), however. She was convinced Charlie

was responsible for just about all the evil in the world to date. She lived in

daily fear of the gangsters and their turf war, though I don't think she was

ever near the line of fire. Every automobile back-fire was a gunshot to her,

and she would scramble the kids to safety. I don't believe she ever met Charlie,

but she hated him so fervently that she couldn't be restrained from attending

his hanging. She wanted to see him swing so she could be sure he was really

gone. He was.

|

|

Yep, those were the good old days—Prohibition days, with Charlie Birger and Shelton gangs. I'm sure that Harrisburg was a much more exciting and interesting place back then than it is today. However, I don't believe I'm alone when I say that while I'd like to see a return of the "good old days," I'd just as soon they left Prohibition, and the Birgers and Sheltons, out.

One

tangible relic of Charlie Birger remains in the family (aside from several old

issues of the Harrisburg Daily Register which my great-grandmother

saved), is one of Charlie's cartridge belts. My father, James

Robert Carr, came into possession of the belt back in the late twenties. It

was given to him by Bill R. Salus (Harrisburg High School, Class of 1931), who

lived next door to the Birgers on West Poplar Street. Apparently Charlie had

given it to Bill as a souvenir after buying a new one. The belt is made of

leather with a dark natural finish and basket-weave tooling.

The

bullet loops are missing, though the belt was intact when my father first

received it. Another of my his friends, “Cowboy” Martin, borrowed the

belt to wear it at the annual Harrisburg Halloween celebration on the square. My

Dad couldn’t remember Martin’s first name, but said they always called him

Cowboy because he liked to dress like a cowboy right up until high school. When

Cowboy returned the belt, it was minus the bullet loops.

|

|

|

|

Gary DeNeal's authoritative biography of Charlie Birger, A Knight of Another Sort, Prohibition Days and Charlie Birger (304 pages, 72 black & white illustrations is available at local bookstores; or paperback $24.95 ppd., from the author at Springhouse Books, P.O. Box 8, Herod, Illinois 62947.

You are visitor No.

since 1 December 2007